|

|

|

How to Think Like a Computer Scientist |  |

Chapter 2

Variables, expressions and statements

2.1 Values and types

A value is one of the fundamental things like a letter or a

number that a program manipulates. The values we have seen so far

are 2 (the result when we added 1 + 1), and

"Hello, World!".

These values belong to different types: 2 is an integer, and "Hello, World!" is a string, so-called because it contains a "string" of letters. You (and the interpreter) can identify strings because they are enclosed in quotation marks.

The print statement also works for integers.

>>> print 4

4

If you are not sure what type a value has, the interpreter can tell you.

>>> type("Hello, World!")

<type 'str'>

>>> type(17)

<type 'int'>

Not surprisingly, strings belong to the type str and integers belong to the type int. Less obviously, numbers with a decimal point belong to a type called float, because these numbers are represented in a format called floating-point.

>>> type(3.2)

<type 'float'>

What about values like "17" and "3.2"? They look like numbers, but they are in quotation marks like strings.

>>> type("17")

<type 'str'>

>>> type("3.2")

<type 'str'>

They're strings.

When you type a large integer, you might be tempted to use commas between groups of three digits, as in 1,000,000. This is not a legal integer in Python, but it is a legal expression:

>>> print 1,000,000

1 0 0

Well, that's not what we expected at all! Python interprets 1,000,000 as a comma-separated list of three integers, which it prints consecutively. This is the first example we have seen of a semantic error: the code runs without producing an error message, but it doesn't do the "right" thing.

2.2 Variables

One of the most powerful features of a programming language is the ability to manipulate variables. A variable is a name that refers to a value.

The assignment statement creates new variables and gives them values:

>>> message = "What's up, Doc?"

>>> n = 17

>>> pi = 3.14159

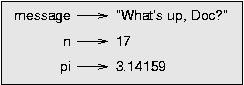

This example makes three assignments. The first assigns the string "What's up, Doc?" to a new variable named message. The second gives the integer 17 to n, and the third gives the floating-point number 3.14159 to pi.

A common way to represent variables on paper is to write the name with an arrow pointing to the variable's value. This kind of figure is called a state diagram because it shows what state each of the variables is in (think of it as the variable's state of mind). This diagram shows the result of the assignment statements:

The print statement also works with variables.

>>> print message

What's up, Doc?

>>> print n

17

>>> print pi

3.14159

In each case the result is the value of the variable. Variables also have types; again, we can ask the interpreter what they are.

>>> type(message)

<type 'str'>

>>> type(n)

<type 'int'>

>>> type(pi)

<type 'float'>

The type of a variable is the type of the value it refers to.

2.3 Variable names and keywords

Programmers generally choose names for their variables that

are meaningful they document what the variable is used for.

Variable names can be arbitrarily long. They can contain both letters and numbers, but they have to begin with a letter. Although it is legal to use uppercase letters, by convention we don't. If you do, remember that case matters. Bruce and bruce are different variables.

The underscore character (_) can appear in a name. It is often used in names with multiple words, such as my_name or price_of_tea_in_china.

If you give a variable an illegal name, you get a syntax error:

>>> 76trombones = "big parade"

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

>>> more$ = 1000000

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

>>> class = "Computer Science 101"

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

76trombones is illegal because it does not begin with a letter. more$ is illegal because it contains an illegal character, the dollar sign. But what's wrong with class?

It turns out that class is one of the Python keywords. Keywords define the language's rules and structure, and they cannot be used as variable names.

Python has twenty-nine keywords:

and def exec if not return

assert del finally import or try

break elif for in pass while

class else from is print yield

continue except global lambda raise

You might want to keep this list handy. If the interpreter complains about one of your variable names and you don't know why, see if it is on this list.

2.4 Statements

A statement is an instruction that the Python interpreter can execute. We have seen two kinds of statements: print and assignment.

When you type a statement on the command line, Python executes it and displays the result, if there is one. The result of a print statement is a value. Assignment statements don't produce a result.

A script usually contains a sequence of statements. If there is more than one statement, the results appear one at a time as the statements execute.

For example, the script

print 1

x = 2

print x

produces the output

1

2

Again, the assignment statement produces no output.

2.5 Evaluating expressions

An expression is a combination of values, variables, and operators. If you type an expression on the command line, the interpreter evaluates it and displays the result:

>>> 1 + 1

2

Although expressions contain values, variables, and operators, not every expression contains all of these elements. A value all by itself is considered an expression, and so is a variable.

>>> 17

17

>>> x

2

Confusingly, evaluating an expression is not quite the same thing as printing a value.

>>> message = "What's up, Doc?"

>>> message

"What's up, Doc?"

>>> print message

What's up, Doc?

When Python displays the value of an expression, it uses the same format you would use to enter a value. In the case of strings, that means that it includes the quotation marks. But the print statement prints the value of the expression, which in this case is the contents of the string.

In a script, an expression all by itself is a legal statement, but it doesn't do anything. The script

17

3.2

"Hello, World!"

1 + 1

produces no output at all. How would you change the script to display the values of these four expressions?

2.6 Operators and operands

Operators are special symbols that represent computations like addition and multiplication. The values the operator uses are called operands.

The following are all legal Python expressions whose meaning is more or less clear:

20+32 hour-1 hour*60+minute minute/60 5**2 (5+9)*(15-7)

The symbols +, -, and /, and the use of parenthesis for grouping, mean in Python what they mean in mathematics. The asterisk (*) is the symbol for multiplication, and ** is the symbol for exponentiation.

When a variable name appears in the place of an operand, it is replaced with its value before the operation is performed.

Addition, subtraction, multiplication, and exponentiation all do what you expect, but you might be surprised by division. The following operation has an unexpected result:

>>> minute = 59

>>> minute/60

0

The value of minute is 59, and in conventional arithmetic 59 divided by 60 is 0.98333, not 0. The reason for the discrepancy is that Python is performing integer division.

When both of the operands are integers, the result must also be an integer, and by convention, integer division always rounds down, even in cases like this where the next integer is very close.

A possible solution to this problem is to calculate a percentage rather than a fraction:

>>> minute*100/60

98

Again the result is rounded down, but at least now the answer is approximately correct. Another alternative is to use floating-point division, which we get to in Chapter 3.

2.7 Order of operations

When more than one operator appears in an expression, the order of evaluation depends on the rules of precedence. Python follows the same precedence rules for its mathematical operators that mathematics does. The acronym PEMDAS is a useful way to remember the order of operations:

- Parentheses have the highest precedence and can be used to force an expression to evaluate in the order you want. Since expressions in parentheses are evaluated first, 2 * (3-1) is 4, and (1+1)**(5-2) is 8. You can also use parentheses to make an expression easier to read, as in (minute * 100) / 60, even though it doesn't change the result.

- Exponentiation has the next highest precedence, so 2**1+1 is 3 and not 4, and 3*1**3 is 3 and not 27.

- Multiplication and Division have the same precedence, which is higher than Addition and Subtraction, which also have the same precedence. So 2*3-1 yields 5 rather than 4, and 2/3-1 is -1, not 1 (remember that in integer division, 2/3=0).

- Operators with the same precedence are evaluated from left to right. So in the expression minute*100/60, the multiplication happens first, yielding 5900/60, which in turn yields 98. If the operations had been evaluated from right to left, the result would have been 59*1, which is 59, which is wrong.

2.8 Operations on strings

In general, you cannot perform mathematical operations on strings, even if the strings look like numbers. The following are illegal (assuming that message has type string):

message-1 "Hello"/123 message*"Hello" "15"+2

Interestingly, the + operator does work with strings, although it does not do exactly what you might expect. For strings, the + operator represents concatenation, which means joining the two operands by linking them end-to-end. For example:

fruit = "banana"

bakedGood = " nut bread"

print fruit + bakedGood

The output of this program is banana nut bread. The space before the word nut is part of the string, and is necessary to produce the space between the concatenated strings.

The * operator also works on strings; it performs repetition. For example, "Fun"*3 is "FunFunFun". One of the operands has to be a string; the other has to be an integer.

On one hand, this interpretation of + and * makes sense by analogy with addition and multiplication. Just as 4*3 is equivalent to 4+4+4, we expect "Fun"*3 to be the same as "Fun"+"Fun"+"Fun", and it is. On the other hand, there is a significant way in which string concatenation and repetition are different from integer addition and multiplication. Can you think of a property that addition and multiplication have that string concatenation and repetition do not?

2.9 Composition

So far, we have looked at the elements of a program variables,

expressions, and statements in isolation, without talking about how to

combine them.

One of the most useful features of programming languages is their ability to take small building blocks and compose them. For example, we know how to add numbers and we know how to print; it turns out we can do both at the same time:

>>> print 17 + 3

20

In reality, the addition has to happen before the printing, so the actions aren't actually happening at the same time. The point is that any expression involving numbers, strings, and variables can be used inside a print statement. You've already seen an example of this:

print "Number of minutes since midnight: ", hour*60+minute

You can also put arbitrary expressions on the right-hand side of an assignment statement:

percentage = (minute * 100) / 60

This ability may not seem impressive now, but you will see other examples where composition makes it possible to express complex computations neatly and concisely.

Warning: There are limits on where you can use certain expressions. For example, the left-hand side of an assignment statement has to be a variable name, not an expression. So, the following is illegal: minute+1 = hour.

2.10 Comments

As programs get bigger and more complicated, they get more difficult to read. Formal languages are dense, and it is often difficult to look at a piece of code and figure out what it is doing, or why.

For this reason, it is a good idea to add notes to your programs to explain in natural language what the program is doing. These notes are called comments, and they are marked with the # symbol:

# compute the percentage of the hour that has elapsed

percentage = (minute * 100) / 60

In this case, the comment appears on a line by itself. You can also put comments at the end of a line:

percentage = (minute * 100) / 60 # caution: integer division

Everything from the # to the end of the line is ignored it

has no effect on the program. The message is intended for the programmer or

for future programmers who might use this code. In this case, it

reminds the reader about the ever-surprising behavior of integer division.

This sort of comment is less necessary if you use the integer division operation, //. It has the same effect as the division operator * Note, but it signals that the effect is deliberate.

percentage = (minute * 100) // 60

The integer division operator is like a comment that says, "I know this is integer division, and I like it that way!"

2.11 Glossary

- value

- A number or string (or other thing to be named later) that can be stored in a variable or computed in an expression.

- type

- A set of values. The type of a value determines how it can be used in expressions. So far, the types you have seen are integers (type int), floating-point numbers (type float), and strings (type string).

- floating-point

- A format for representing numbers with fractional parts.

- variable

- A name that refers to a value.

- statement

- A section of code that represents a command or action. So far, the statements you have seen are assignments and print statements.

- assignment

- A statement that assigns a value to a variable.

- state diagram

- A graphical representation of a set of variables and the values to which they refer.

- keyword

- A reserved word that is used by the compiler to parse a program; you cannot use keywords like if, def, and while as variable names.

- operator

- A special symbol that represents a simple computation like addition, multiplication, or string concatenation.

- operand

- One of the values on which an operator operates.

- expression

- A combination of variables, operators, and values that represents a single result value.

- evaluate

- To simplify an expression by performing the operations in order to yield a single value.

- integer division

- An operation that divides one integer by another and yields an integer. Integer division yields only the whole number of times that the numerator is divisible by the denominator and discards any remainder.

- rules of precedence

- The set of rules governing the order in which expressions involving multiple operators and operands are evaluated.

- concatenate

- To join two operands end-to-end.

- composition

- The ability to combine simple expressions and statements into compound statements and expressions in order to represent complex computations concisely.

- comment

- Information in a program that is meant for other programmers (or anyone reading the source code) and has no effect on the execution of the program.

Warning: the HTML version of this document is generated from Latex and may contain translation errors. In particular, some mathematical expressions are not translated correctly.

|

|

|

How to Think Like a Computer Scientist |  |