| Purchase | Copyright © 2002 Paul Sheer. Click here for copying permissions. | Home |

|

| |

The following introduction is quoted from the Samba online documentation.

A lot of emphasis has been placed on peaceful coexistence between UNIX and Windows. Unfortunately, the two systems come from very different cultures and they have difficulty getting along without mediation. ...and that, of course, is Samba's job. Samba <http://samba.org/> runs on UNIX platforms, but speaks to Windows clients like a native. It allows a UNIX system to move into a Windows ``Network Neighborhood'' without causing a stir. Windows users can happily access file and print services without knowing or caring that those services are being offered by a UNIX host.

All of this is managed through a protocol suite which is currently known as the ``Common Internet File System,'' or CIFS <http://www.cifs.com>. This name was introduced by Microsoft, and provides some insight into their hopes for the future. At the heart of CIFS is the latest incarnation of the Server Message Block (SMB) protocol, which has a long and tedious history. Samba is an open source CIFS implementation, and is available for free from the http://samba.org/ mirror sites.

Samba and Windows are not the only ones to provide CIFS networking. OS/2 supports SMB file and print sharing, and there are commercial CIFS products for Macintosh and other platforms (including several others for UNIX). Samba has been ported to a variety of non-UNIX operating systems, including VMS, AmigaOS, and NetWare. CIFS is also supported on dedicated file server platforms from a variety of vendors. In other words, this stuff is all over the place.

It started a long time ago, in the early days of the PC, when IBM and Sytec co-developed a simple networking system designed for building small LANs. The system included something called NetBIOS, or Network Basic Input Output System. NetBIOS was a chunk of software that was loaded into memory to provide an interface between programs and the network hardware. It included an addressing scheme that used 16-byte names to identify workstations and network-enabled applications. Next, Microsoft added features to DOS that allowed disk I/O to be redirected to the NetBIOS interface, which made disk space sharable over the LAN. The file-sharing protocol that they used eventually became known as SMB, and now CIFS.

Lots of other software was also written to use the NetBIOS API (Application Programmer's Interface), which meant that it would never, ever, ever go away. Instead, the workings beneath the API were cleverly gutted and replaced. NetBEUI (NetBIOS Enhanced User Interface), introduced by IBM, provided a mechanism for passing NetBIOS packets over Token Ring and Ethernet. Others developed NetBIOS LAN emulation over higher-level protocols including DECnet, IPX/SPX and, of course, TCP/IP.

NetBIOS and TCP/IP made an interesting team. The latter could be routed between interconnected networks (internetworks), but NetBIOS was designed for isolated LANs. The trick was to map the 16-byte NetBIOS names to IP addresses so that messages could actually find their way through a routed IP network. A mechanism for doing just that was described in the Internet RFC1001 and RFC1002 documents. As Windows evolved, Microsoft added two additional pieces to the SMB package. These were service announcement, which is called ``browsing,'' and a central authentication and authorization service known as Windows NT Domain Control.

Andrew Tridgell, who is both tall and Australian, had a bit of a problem. He needed to mount disk space from a UNIX server on his DOS PC. Actually, this wasn't the problem at all because he had an NFS (Network File System) client for DOS and it worked just fine. Unfortunately, he also had an application that required the NetBIOS interface. Anyone who has ever tried to run multiple protocols under DOS knows that it can be...er...quirky.

So Andrew chose the obvious solution. He wrote a packet sniffer, reverse engineered the SMB protocol, and implemented it on the UNIX box. Thus, he made the UNIX system appear to be a PC file server, which allowed him to mount shared filesystems from the UNIX server while concurrently running NetBIOS applications. Andrew published his code in early 1992. There was a quick, but short succession of bug-fix releases, and then he put the project aside. Occasionally he would get email about it, but he otherwise ignored it. Then one day, almost two years later, he decided to link his wife's Windows PC with his own Linux system. Lacking any better options, he used his own server code. He was actually surprised when it worked.

Through his email contacts, Andrew discovered that NetBIOS and SMB were actually (though nominally) documented. With this new information at his fingertips he set to work again, but soon ran into another problem. He was contacted by a company claiming trademark on the name that he had chosen for his server software. Rather than cause a fuss, Andrew did a quick scan against a spell-checker dictionary, looking for words containing the letters ``smb''. ``Samba'' was in the list. Curiously, that same word is not in the dictionary file that he uses today. (Perhaps they know it's been taken.)

The Samba project has grown mightily since then. Andrew now has a whole team of programmers, scattered around the world, to help with Samba development. When a new release is announced, thousands of copies are downloaded within days. Commercial systems vendors, including Silicon Graphics, bundle Samba with their products. There are even Samba T-shirts available. Perhaps one of the best measures of the success of Samba is that it was listed in the ``Halloween Documents'', a pair of internal Microsoft memos that were leaked to the Open Source community. These memos list Open Source products which Microsoft considers to be competitive threats. The absolutely best measure of success, though, is that Andrew can still share the printer with his wife.

Samba consists of two key programs, plus a bunch of other stuff that we'll get to later. The two key programs are smbd and nmbd. Their job is to implement the four basic modern-day CIFS services, which are:

File and print services are, of course, the cornerstone of the CIFS suite. These are provided by smbd, the SMB daemon. Smbd also handles ``share mode'' and ``user mode'' authentication and authorization. That is, you can protect shared file and print services by requiring passwords. In share mode, the simplest and least recommended scheme, a password can be assigned to a shared directory or printer (simply called a ``share''). This single password is then given to everyone who is allowed to use the share. With user mode authentication, each user has their own username and password and the System Administrator can grant or deny access on an individual basis.

The Windows NT Domain system provides a further level of authentication refinement for CIFS. The basic idea is that a user should only have to log in once to have access to all of the authorized services on the network. The NT Domain system handles this with an authentication server, called a Domain Controller. An NT Domain (which should not be confused with a Domain Name System (DNS) Domain) is basically a group of machines which share the same Domain Controller.

The NT Domain system deserves special mention because, until the release of Samba version 2, only Microsoft owned code to implement the NT Domain authentication protocols. With version 2, Samba introduced the first non-Microsoft-derived NT Domain authentication code. The eventual goal, of course, it to completely mimic a Windows NT Domain Controller.

The other two CIFS pieces, name resolution and browsing, are handled by nmbd. These two services basically involve the management and distribution of lists of NetBIOS names.

Name resolution takes two forms: broadcast and point-to-point. A machine may use either or both of these methods, depending upon its configuration. Broadcast resolution is the closest to the original NetBIOS mechanism. Basically, a client looking for a service named Trillian will call out ``Yo! Trillian! Where are you?'', and wait for the machine with that name to answer with an IP address. This can generate a bit of broadcast traffic (a lot of shouting in the streets), but it is restricted to the local LAN so it doesn't cause too much trouble.

The other type of name resolution involves the use of an NBNS (NetBIOS Name Service) server. (Microsoft called their NBNS implementation WINS, for Windows Internet Name Service, and that acronym is more commonly used today.) The NBNS works something like the wall of an old-fashioned telephone booth. (Remember those?) Machines can leave their name and number (IP address) for others to see.

Hi, I'm node Voomba. Call me for a good time! 192.168.100.101

It works like this: The clients send their NetBIOS names and IP addresses to the NBNS server, which keeps the information in a simple database. When a client wants to talk to another client, it sends the other client's name to the NBNS server. If the name is on the list, the NBNS hands back an IP address. You've got the name, look up the number.

Clients on different subnets can all share the same NBNS server so, unlike broadcast, the point-to-point mechanism is not limited to the local LAN. In many ways the NBNS is similar to the DNS, but the NBNS name list is almost completely dynamic and there are few controls to ensure that only authorized clients can register names. Conflicts can, and do, occur fairly easily.

Finally, there's browsing. This is a whole 'nother kettle of worms, but Samba's nmbd handles it anyway. This is not the web browsing we know and love, but a browsable list of services (file and print shares) offered by the computers on a network.

On a LAN, the participating computers hold an election to decide which of them will become the Local Master Browser (LMB). The ``winner'' then identifies itself by claiming a special NetBIOS name (in addition to any other names it may have). The LMB's job is to keep a list of available services, and it is this list that appears when you click on the Windows ``Network Neighborhood'' icon.

In addition to LMBs, there are Domain Master Browsers (DMBs). DMBs coordinate browse lists across NT Domains, even on routed networks. Using the NBNS, an LMB will locate its DMB to exchange and combine browse lists. Thus, the browse list is propagated to all hosts in the NT Domain. Unfortunately, the synchronization times are spread apart a bit. It can take more than an hour for a change on a remote subnet to appear in the Network Neighborhood.

Samba comes with a variety of utilities. The most commonly used are:

There are more, of course, but describing them would require explaining even more bits and pieces of CIFS, SMB, and Samba. That's where things really get tedious, so we'll leave it alone for now.

One of the cool things that you can do with a Windows box is use an SMB file share as if it were a hard disk on your own machine. The N: drive can look, smell, feel, and act like your own disk space, but it's really disk space on some other computer somewhere else on the network.

Linux systems can do this too, using the smbfs filesystem. Built from Samba code, smbfs (which stands for SMB Filesystem) allows Linux to map a remote SMB share into its directory structure. So, for example, the /mnt/zarquon directory might actually be an SMB share, yet you can read, write, edit, delete, and copy the files in that directory just as you would local files.

The smbfs is nifty, but it only works with Linux. In fact, it's not even part of the Samba suite. It is distributed with Samba as a courtesy and convenience. A more general solution is the new smbsh (SMB shell, which is still under development at the time of this writing). This is a cool gadget. It is run like a UNIX shell, but it does some funky fiddling with calls to UNIX libraries. By intercepting these calls, smbsh can make it look as though SMB shares are mounted. All of the read, write, etc. operations are available to the smbsh user. Another feature of smbsh is that it works on a per user, per shell basis, while mounting a filesystem is a system-wide operation. This allows for much finer-grained access controls.

Samba is configured using the smb.conf file. This is a simple text file designed to look a lot like those *.ini files used in Windows. The goal, of course, is to give network administrators familiar with Windows something comfortable to play with. Over time, though, the number of things that can be configured in Samba has grown, and the percentage of Network Admins willing to edit a Windows *.ini file has shrunk. For some people, that makes managing the smb.conf file a bit daunting.

Still, learning the ins and outs of smb.conf is a worthwhile penance. Each of the smb.conf variables has a purpose, and a lot of fine-tuning can be accomplished. The file structure contents are fully documented, so as to give administrators a running head start, and smb.conf can be manipulated using swat, which at least makes it nicer to look at.

Samba 2.0 was released in January 1999. One of the most significant and cool features of the 2.0 release was improved speed. Ziff-Davis Publishing used their Netbench software to benchmark Samba 2.0 on Linux against Windows NT4. They ran all of their tests on the same PC hardware, and their results showed Samba's throughput under load to be at least twice that of NT. Samba is shipped with all major Linux distributions, and Ziff-Davis tested three of those.

Another milestone was reached when Silicon Graphics (SGI) became the first commercial UNIX vendor to support Samba. In their December 1998 press release, they claimed that their Origin series servers running Samba 2.0 were the most powerful line of file servers for Windows clients available. SGI now offers commercial support for Samba as do several other providers, many of which are listed on the Samba web site (see http://samba.org/). Traditional Internet support is, of course, still available via the comp.protocols.smb newsgroup and the [email protected] mailing list.

The Samba Team continues to work on new goodies. Current interests include NT ACLs (Access Control Lists), support for LDAP (the Lightweight Directory Access Protocol), NT Domain Control, and Microsoft's DFS (Distributed File System).

Windows 2000 looms on the horizon like a lazy animal peeking its head over the edge of its burrow while trying to decide whether or not to come out. No one is exactly sure about the kind of animal it will be when it does appear, but folks are fairly certain that it will have teeth.

Because of their dominance on the desktop, Microsoft gets to decide how CIFS will grow. Windows 2000, like previous major operating system releases, will give us a whole new critter to study. Based on the beta copies and the things that Microsoft has said, here are some things to watch for:

One certainty is that W2K (as it is often called) is, and will be, under close scrutiny. Windows has already attracted the attention of some of the Internet Wonderland's more curious inhabitants, including security analysts, standards groups, crackers dens, and general all-purpose geeks. The business world, which has finally gotten a taste of the freedom of Open Source Software, may be reluctant to return to the world of proprietary, single-vendor solutions. Having the code in your hands is both reassuring and empowering.

Whatever the next Windows animal looks like, it will be Samba's job to help it get along with its peers in the diverse world of the Internet. The Samba Team, a microcosm of the Internet community, are among those watching W2K to see how it develops. Watching does not go hand-in-hand with waiting, though, and Samba is an on-going and open effort. Visit the Samba web site, join the mailing lists, and see what's going on.

Participate in the future.

That said, configuring smbd is really easy. A typical LAN will require a UNIX machine that can share /home/* directories to Windows clients, where each user can log in as the name of their home directory. It must also act as a print share that redirects print jobs through lpr; and then in PostScript, the way we like it. Consider a Windows machine divinian.cranzgot.co.za on a local LAN 192.168.3.0/24. The user of that machine would have a UNIX login psheer on the server cericon.cranzgot.co.za.

The usual place for Samba's configuration file is /etc/samba/smb.conf on most distributions. A minimalist configuration file to perform the above functions might be:

5 10 15 20 |

[global] workgroup = MYGROUP server string = Samba Server hosts allow = 192.168. 127. printcap name = /etc/printcap load printers = yes printing = bsd log file = /var/log/samba/%m.log max log size = 0 security = user socket options = TCP_NODELAY SO_RCVBUF=8192 SO_SNDBUF=8192 encrypt passwords = yes smb passwd file = /etc/samba/smbpasswd[homes] comment = Home Directories browseable = no writable = yes[printers] comment = All Printers path = /var/spool/samba browseable = no guest ok = no printable = yes |

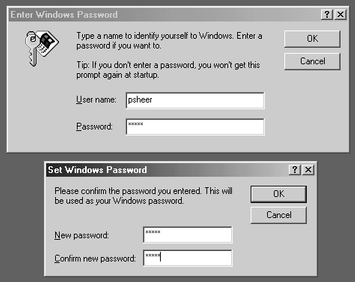

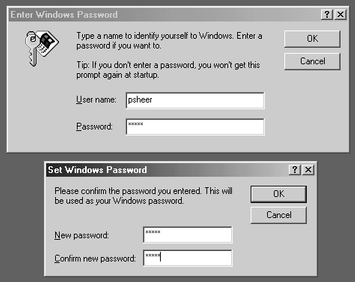

The SMB protocol stores passwords differently from UNIX. It therefore needs its own password file, usually /etc/samba/smbpasswd. There is also a mapping between UNIX logins and Samba logins in /etc/samba/smbusers, but for simplicity we will use the same UNIX name as the Samba login name. We can add a new UNIX user and Samba user and set both their passwords with

|

smbadduser psheer:psheeruseradd psheersmbpasswd psheerpasswd psheer |

Note that with SMB there are all sorts of issues with case interpretation--an incorrectly typed password could still work with Samba but obviously won't with UNIX.

To start Samba, run the familiar

|

/etc/init.d/smbd start( /etc/rc.d/init.d/smbd start )( /etc/init.d/samba start ) |

For good measure, there should also be a proper DNS configuration with forward and reverse lookups for all client machines.

At this point you can test your Samba server from the UNIX side. LINUX has native support for SMB shares with the smbfs file system. Try mounting a share served by the local machine:

|

mkdir -p /mnt/smbmount -t smbfs -o username=psheer,password=12345 //cericon/psheer /mnt/smb |

You can now run tail -f /var/log/samba/cericon.log. It should contain messages like:

|

cericon (192.168.3.2) connect to service psheer as user psheer (uid=500, gid=500) (pid 942) |

where a ``service'' means either a directory share or a print share.

The useful utility smbclient is a generic tool for running SMB requests, but is mostly useful for printing. Make sure your printer daemon is running (and working) and then try

|

echo hello | smbclient //cericon/lp 12345 -U psheer -c 'print -' |

which will create a small entry in the lp print queue. Your log file will be appended with:

|

cericon (192.168.3.2) connect to service lp as user psheer (uid=500, gid=500) (pid 1014) |

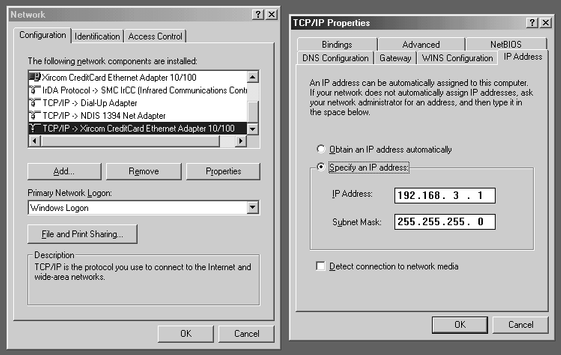

Configuration from Windows begins with a working TCP/IP configuration:

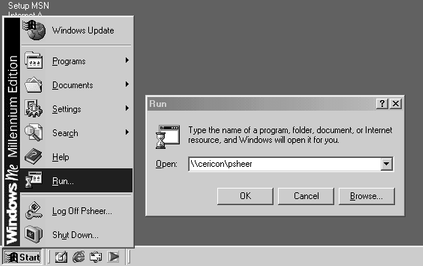

Finally, go to Run... in the Start menu and enter \\cericon\psheer. You will be prompted for a password, which you should enter as for the smbpasswd program above.

Under Settings in your Start menu, you can add new printers. Your UNIX lp print queue is visible as the \\cericon\lp network printer and should be entered as such in the configuration wizard. For a printer driver, you should choose ``Apple Color Laserwriter,'' since this driver just produces regular PostScript output. In the printer driver options you should also select to optimize for ``portability.''

swat is a service, run from inetd, that listens for HTTP connections on port 901. It allows complete remote management of Samba from a web browser. To configure, add the service swat 901/tcp to your /etc/services file, and the following to your /etc/inetd.conf file.

|

swat stream tcp nowait root /usr/sbin/tcpd /usr/sbin/swat |

being very careful who you allow connections from. If you are running xinetd, create a file /etc/xinetd.d/swat:

5 10 |

service swat{ port = 901 socket_type = stream wait = no only_from = localhost 192.168.0.0/16 user = root server = /usr/sbin/swat server_args = -s /etc/samba/smb.conf log_on_failure += USERID disable = no} |

After restarting inetd (or xinetd), you can point your web browser to http://cericon:901/. Netscape will request a user and password. You should login as root ( swat does not use smbpasswd to authenticate this login). The web page interface is extremely easy to use--

Windows SMB servers compete to be the name server of their domain by version number and uptime. By this we again mean the Windows name service and not the DNS service. How exactly this works I will not cover here, [Probably because I have no idea what I am talking about.]but do be aware that configuring a Samba server on a network of many NT machines and getting it to work can be a nightmare. A solution once attempted was to shut down all machines on the LAN, then pick one as the domain server, then bring it up first after waiting an hour for all possible timeouts to have elapsed. After verifying that it was working properly, the rest of the machines were booted.

Then of course, don't forget your nmblookup command.