Serializing Complex Objects with Fuel

Fuel is a fast open-source general-purpose binary object serialization framework developed by Mariano Martinez-Peck, Martìn Dias and Max Leske. It is robust and used in many industrial cases. A fundamental reason for the creation of Fuel was speed: while there is a plethora of frameworks to serialize objects based on recursive parsing of the object graphs in textual format as XML, JSON, or STON, these approaches are often slow. (For JSON and STON see also Chapters STON and NeoJSON.)

Part of the speed of Fuel comes from the idea that objects are loaded more often than stored. This makes it worth to spend more time while storing to yield faster loading. Also, its storage scheme is based on the pickle format that puts similar objects into groups for efficiency and performance. As a result, Fuel has been shown to be one of the fastest object loaders, while still being a really fast object saver. Moreover, Fuel can serialize nearly any object in the image, it can even serialize a full execution stack and later reload it!

The main features of Fuel are as follows:

- It has an object-oriented design.

- It does not need special VM-support.

- It is modularly packaged.

- It can serialize/materialize not only plain objects but also classes, traits, methods, closures, contexts, packages, etc.

- It supports global references.

- It is very customizable: you can ignore certain instance variables, substitute objects by others, define pre and post serialization and materialization actions, etc.

- It supports class renaming and class reshaping.

- It has good test coverage and a large suite of benchmarks.

1. General Information

Fuel has been developed and maintained over the years by the following people: Martin Dias, Mariano Martinez Peck, Max Leske, Pavel Krivanek, Tristan Bourgois and Stéphane Ducasse (as PhD advisor and financer).

The idea of Fuel was developed by Mariano Martinez Peck based on the work by Eliot Miranda who worked on the "parcels" implementation for VisualWorks. Eliot's work again was based on the original "parcels" implementation by David Leib. "Parcels" demonstrates very nicely that the binary pickle format can be a good alternative to textual storage and that grouping of objects makes a lot of sense in object oriented systems.

Before going into details we present the ideas behind Fuel and it's main features and give basic usage examples.

1.1. Goals

- Concrete

- Fuel doesn't aspire to have a dialect-interchange format. This makes it possible to serialize special objects like contexts, block closures, exceptions, compiled methods and classes. Although there are ports to other dialects, most notably Squeak, Fuel development is Pharo-centric.

- Flexible

- Depending on the context, there can be multiple ways of serializing the same object. For example, a class can be considered either a global or a regular object. In the former case, references to the class will be encoded by name and the class is expected to be part of the environment upon materialization; in the latter case, the class will be encoded in detail, with its method dictionary, etc.

- Fast

- Fuel has been designed for performance. Fuel comes with a complete benchmark suite to help analyse the performance with diverse sample sets, as well as to compare it against other serializers. Fuel's pickling algorithm achieves outstanding materialization performance, as well as very good serialization performance, even when compared to other binary formats such as ImageSegment.

- Object-Oriented

- A requirement from the onset was to have a good object-oriented design and to avoid special support from the virtual machine.

- Maintainable

- Fuel has a complete test suite (over 600 unit tests), with a high degree of code coverage. Fuel also has well-commented classes and methods.

1.2. Installation and Demo

Fuel 1.9 is available by default in Pharo since version 2.0 of Pharo. Therefore you do not need to install it. The default packages work out of the box in Pharo 1.1.1, 1.1.2, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, 2.0, 3.0 and 4.0 and Squeak 4.1, 4.2, 4.3, 4.4, 4.5. The stable version at the time of writing is 1.9.4.

Open the Transcript and execute the code below in a Playground. This example serializes a set, the default Transcript (which is a global) and a

block. On materialization it shows that

- the set is correctly recreated,

- the global

Transcriptis still the same instance (hasn't been modified) - and the block can be evaluated properly.

| arrayToSerialize materializedArray |

arrayToSerialize :=

Array

with: (Set with: 42)

with: Transcript

with: [ :aString | Transcript show: aString; cr ].

"Store (serialize)"

FLSerializer serialize: arrayToSerialize toFileNamed: 'demo.fuel'.

"Load (materialize)"

materializedArray := FLMaterializer materializeFromFileNamed: 'demo.fuel'.

Transcript

show: 'The sets are equal: ';

show: arrayToSerialize first = materializedArray first;

cr;

show: 'But not the same: ';

show: arrayToSerialize first ~~ materializedArray first;

cr;

show: 'The global value Transcript is the same: ';

show: arrayToSerialize second == materializedArray second;

cr.

materializedArray third

value: 'The materialized block closure can be properly evaluated.'.1.3. Some Links

- The home page is http://rmod.inria.fr/web/software/Fuel.

- The source code is at http://smalltalkhub.com/#!/~Pharo/Fuel.

- The CI job is at https://ci.inria.fr/pharo-contribution/job/Fuel-Stable/.

2. Getting Started

2.1. Basic Examples

Fuel offers some class-side messages to ease more common uses of

serialization (the serialize:toFileNamed: message )

and materialization (the message materializeFromFileNamed:). The next example writes to and reads from a file:

FLSerializer serialize: 'stringToSerialize' toFileNamed: 'demo.fuel'.

materializedString := FLMaterializer materializeFromFileNamed: 'demo.fuel'.

Fuel also provides messages for storing into a ByteArray, namely

the messages serializeToByteArray: and materializeFromByteArray:. This

can be interesting, for example, for serializing an object graph as a

blob of data into a database when using Voyage (see Chapter Voyage).

anArray := FLSerializer serializeToByteArray: 'stringToSerialize'.

materializedString := FLMaterializer materializeFromByteArray: anArray.2.2. FileStream

In the following example we work with file streams. Note that the stream needs to be set to binary mode:

'demo.fuel' asFileReference writeStreamDo: [ :aStream |

FLSerializer newDefault

serialize: 'stringToSerialize'

on: aStream binary ].

'demo.fuel' asFileReference readStreamDo: [ :aStream |

materializedString := (FLMaterializer newDefault

materializeFrom: aStream binary) root ].

In this example, we are no longer using the class-side messages. Now,

for both FLSerializer and FLMaterializer, we first create

instances by sending the

newDefault message and then perform the desired operations. As we will see in the next example, creating the instances allows for more flexibility on serialization

and materialization.

2.3. Compression

Fuel does not care to what kind of stream it writes its data. This makes it easy to use stream compressors. An example of use is as follows:

'number.fuel.zip' asFileReference writeStreamDo: [ :aFileStream |

|gzip|

aFileStream binary.

gzip := GZipWriteStream on: aFileStream.

FLSerializer newDefault serialize: 123 on: gzip.

gzip close ].

'number.fuel.zip' asFileReference readStreamDo: [ :aFileStream |

|gzip|

aFileStream binary.

gzip := GZipReadStream on: aFileStream.

materializedString := (FLMaterializer newDefault

materializeFrom: gzip) root.

gzip close ].2.4. Showing a Progress Bar

Sometimes it is nice to see progress updates on screen. Use the message showProgress in this case. The progress bar functionality is available from the

FuelProgressUpdate package, so load that first:

Gofer it

url: 'http://smalltalkhub.com/mc/Pharo/Fuel/main';

package: 'ConfigurationOfFuel';

load.

(ConfigurationOfFuel project version: #stable)

load: 'FuelProgressUpdate'.

The following example uses the message showProgress to display a progress bar during operations.

'numbers.fuel' asFileReference writeStreamDo: [ :aStream |

FLSerializer newDefault

showProgress;

serialize: (1 to: 200000) asArray

on: aStream binary ].

'numbers.fuel' asFileReference readStreamDo: [ :aStream |

materializedString :=

(FLMaterializer newDefault

showProgress;

materializeFrom: aStream binary) root ].3. Managing Globals

Sometimes we may be interested in storing just the name of a reference,

because we know it will be present when materializing the graph. For example when the current processor scheduler Processor is referenced from the graph we do not want to serialize it as it does not make sense to materialize it. Hence Fuel considers some objects as globals that may not be serialized. It also allows for you to add to this set and lastly to use a different environment when materializing globals.

3.1. Default Globals

By default, Fuel considers the following objects as globals, i.e., it will store just their name:

nil,true,false, andSmalltalk globals.- Any

Class,Trait,MetaclassorClassTrait. - Any

CompiledMethod, except when either it answers false to the messageisInstalledor true to the messageisDoIt. The latter happens, for example, if this is code evaluated from a Workspace. - Some well-known global variables:

Smalltalk,SourceFiles,Transcript,Undeclared,Display,TextConstants,ActiveWorld,ActiveHand,ActiveEvent,Sensor,Processor,ImageImports,SystemOrganizationandWorld.

3.2. Duplication of Custom Globals

With this following code snippet, we show that by default a Smalltalk global value is not serialized as a global. In such a case it is duplicated on materialization.

"Define a global variable named SomeGlobal."

SomeGlobal := Set new.

"Serialize and materialize the value of SomeGlobal."

FLSerializer

serialize: SomeGlobal

toFileNamed: 'g.fuel'.

"The materialized object *is not* the same as the global instance."

[ (FLMaterializer materializeFromFileNamed: 'g.fuel') ~~ SomeGlobal ] assert.

We can tell Fuel to handle a new global and how to avoid global duplication on materialization. The message considerGlobal: is used to specify that an

object should be stored as global, i.e. it should only be referenced by name.

| aSerializer |

"Define a global variable named SomeGlobal."

SomeGlobal := Set new.

aSerializer := FLSerializer newDefault.

"Tell the serializer to consider SomeGlobal as global."

aSerializer analyzer considerGlobal: #SomeGlobal.

aSerializer

serialize: SomeGlobal

toFileNamed: 'g.fuel'.

"In this case, the materialized object *is* the same as the global instance."

[ (FLMaterializer materializeFromFileNamed: 'g.fuel') == SomeGlobal ] assert.3.3. Changing the Environment

The default lookup location for globals is Smalltalk globals. This can be changed by using the message globalEnvironment: during serialization and

materialization.

The following example shows how to change the globals environment during materialization. It creates a global containing the empty set, tells Fuel to consider

it as a global and serializes it to disk. A new environment is then created with a different value for the global: 42 and the global is then materialized in

this environment. We see that the materialized global has as value 42, i.e. the value of the environment in which it is materialized.

| aSerializer aMaterializer anEnvironment |

"Define a global variable named SomeGlobal."

SomeGlobal := Set new.

"Tell the serializer to consider SomeGlobal as global."

aSerializer := FLSerializer newDefault.

aSerializer analyzer considerGlobal: #SomeGlobal.

aSerializer

serialize: SomeGlobal

toFileNamed: 'g.fuel'.

"Override value for SomeGlobal."

anEnvironment := Dictionary newFrom: Smalltalk globals.

anEnvironment at: #SomeGlobal put: {42}.

"In this case, the materialized object *is the same* as the global instance."

'g.fuel' asFileReference readStreamDo: [ :aStream |

| materializedGlobal |

aStream binary.

aMaterializer := FLMaterializer newDefault.

"Set the environment"

aMaterializer globalEnvironment: anEnvironment.

materializedGlobal := (aMaterializer materializeFrom: aStream) root.

[ materializedGlobal = {42} ] assert.

[ materializedGlobal == (anEnvironment at: #SomeGlobal) ] assert ].4. Customizing the Graph

When serializing an object you often want to select which part of the object's state should be serialized. To achieve this with Fuel you can selectively ignore instance variables.

4.1. Ignoring Instance Variables

Under certain conditions it may be desirable to prevent serialization of certain instance variables for a given class. A straightforward way to do this is to

override the hook method fuelIgnoredInstanceVariableNames, at class side of the given class. It returns an array of instance variable names (as symbols) and

all instances of the class will be serialized without these instance variables.

For example, let's say we have the class User and we do not want to serialize the instance variables 'accumulatedLogins' and 'applications'. So we

implement:

User class>>fuelIgnoredInstanceVariableNames

^ #('accumulatedLogins' 'applications')4.2. Post-Materialization Action

When materialized, ignored instance variables will be nil. To re-initialize and set values to those instance variables, send the

fuelAfterMaterialization message.

The message fuelAfterMaterialization lets you execute some action once an object has been materialized. For example, let's say we would like to set back the

instance variable 'accumulatedLogins' during materialization. We can implement:

User>>fuelAfterMaterialization

accumulatedLogins := 0.4.3. Substitution on Serialization

Sometimes it is useful to serialize something different than the original object, without altering the object itself. Fuel proposes two different ways to do this: dynamically and statically.

4.3.1. Dynamically

You can establish a specific substitution for a particular serialization. Let's illustrate with an example, where the graph includes a Stream and you want

to serialize nil instead.

objectToSerialize := { 'hello' . '' writeStream}.

'demo.fuel' asFileReference writeStreamDo: [ :aStream |

aSerializer := FLSerializer newDefault.

aSerializer analyzer

when: [ :object | object isStream ]

substituteBy: [ :object | nil ].

aSerializer

serialize: objectToSerialize

on: aStream binary ].

'demo.fuel' asFileReference readStreamDo: [ :aStream |

materializedObject := (FLMaterializer newDefault

materializeFrom: aStream binary) root]

After executing this code, materializedObject will contain #('hello' nil), i.e. without the instance of a Stream.

4.3.2. Statically

You can also do substitution for each serialization of an object by overriding its fuelAccept: method. Fuel visits each object in the graph by sending this

message to determine how to trace and serialize it. The argument of the message is an instance of a FLMapper subclass.

As an example, imagine we want to replace an object directly with nil. In other words, we want to make all objects of a class transient, for example all

CachedResult instances. For that, we should implement:

CachedResult>>fuelAccept: aGeneralMapper

^ aGeneralMapper

visitSubstitution: self

by: nil

As another example, we have a Proxy class and when serializing we want to serialize its target instead of the proxy. So we redefine fuelAccept: as

follows:

Proxy>>fuelAccept: aGeneralMapper

^ aGeneralMapper

visitSubstitution: self

by: target

The use of fuelAccept: also allows for deciding about serialization conditionally. For example, we have the class User and we want to nil the

instance variable history when its size is greater than 100. A naive implementation is as follows:

User>>fuelAccept: aGeneralMapper

^ self history size > 100

ifTrue: [

aGeneralMapper

visitSubstitution: self

by: (self copy history: #()) ].

ifFalse: [ super fuelAccept: aGeneralMapper ]We are substituting the original user by another instance of User, which Fuel will visit with the same fuelAccept: method. Because of this we fall into an infinite sequence of substitutions!

Using fuelAccept: we can easily fall into an infinite sequence of substitutions. To avoid this problem, the message visitSubstitution:by:onRecursionDo:

should be used. In it, an alternative mapping is provided for the case of mapping an object which is already a substitute of another one. The example above

should be written as follows:

User>>fuelAccept: aGeneralMapper

aGeneralMapper

visitSubstitution: self

by: (self copy history: #())

onRecursionDo: [ super fuelAccept: aGeneralMapper ]In this case, the substituted user (i.e., the one with the empty history) will be visited via its super implementation.

4.4. Substitution on Materialization

In the same way that we may want to customize object serialization, we may want to customize object materialization. This can be done either by treating an object as a globally obtained reference, or by hooking into instance creation.

4.4.1. Global References

Suppose we have a special instance of User that represents the admin user, and it is a unique instance in the image. In the case that the admin user is

referenced in our graph, we want to get that object from a global when the graph is materialized. This can be achieved by modifying the serialization

process as follows:

User>>fuelAccept: aGeneralMapper

^ self == User admin

ifTrue: [

aGeneralMapper

visitGlobalSend: self

name: #User

selector: #admin ]

ifFalse: [ super fuelAccept: aGeneralMapper ]

During serialization the admin user won't be serialized but instead its global name and selector are stored. Then, at materialization time, Fuel will send the

message admin to the class User, and use the returned value as the admin user of the materialized graph.

4.4.2. Hooking into Instance Creation

Fuel provides two hook methods to customise how instances are created: fuelNew and fuelNew:.

For (regular) fixed objects, the method fuelNew is defined in Behavior as:

fuelNew

^ self basicNewBut we can override it to our needs, for example:

fuelNew

^ self uniqueInstance

This similarly applies to variable sized objects through the method fuelNew: which by default sends basicNew:.

4.5. Not Serializable Objects

You may want to make sure that some objects are not part of the graph during serialization. Fuel provides the hook method named visitNotSerializable: which

signals an FLNotSerializable exception if such an object is found in the graph that is to be serialized.

MyNotSerializableObject>>fuelAccept: aGeneralMapper

aGeneralMapper visitNotSerializable: self5. Errors

We provide a hierarchy of errors which allows one to clearly identify the problem when something went wrong:

FLErrorFLSerializationErrorFLNotSerializableFLObjectNotFoundFLObsolete

FLMaterializationErrorFLBadSignatureFLBadVersionFLClassNotFoundFLGlobalNotFoundFLMethodChangedFLMethodNotFound

As most classes of Fuel, they have class comments that explain their purpose:

- FLError

- I represent an error produced during Fuel operation.

- FLSerializationError

- I represent a serialization error.

- FLNotSerializable

- I represent an error which may happen while tracing in the graph an object that is forbidden of being serialized.

- FLObjectNotFound

- I represent an error which may happen during serialization, when trying to encode on the stream a reference to an object that should be encoded before, but it is not. This usually happens when the graph changes during serialization. Another possible cause is a bug in the analysis step of serialization.

- FLObsolete

- I am an error produced during serialization, signaled when trying to serialize an obsolete class as global. It is a prevention, because such class is likely to be absent during materialization.

- FLMaterializationError

- I represent a materialization error.

- FLBadSignature

- I represent an error produced during materialization when the serialized signature doesn't match the materializer's signature (accessible via

FLMaterializer>>signature). A signature is a byte prefix that should prefix a well-serialized stream.

- FLBadVersion

- I represent an error produced during materialization when the serialized version doesn't match the materializer's version (accessible via

FLMaterializer>>version). A version is encoded in 16 bits and is encoded heading the serialized stream, after the signature.

- FLClassNotFound

- I represent an error produced during materialization when a serialized class or trait name doesn't exist.

- FLGlobalNotFound

- I represent an error produced during materialization when a serialized global name doesn't exist (at

Smalltalk globals).

- FLMethodChanged

- I represent an error produced during materialization when a change in the bytecodes of a method serialized as global is detected. This error was born when testing the materialization of a

BlockClosuredefined in a method that changed. The test produced a VM crash.

- FLMethodNotFound

- I represent an error produced during materialization when a serialized method in a class or trait name doesn't exist (in

Smalltalk globals).

6. Object Migration

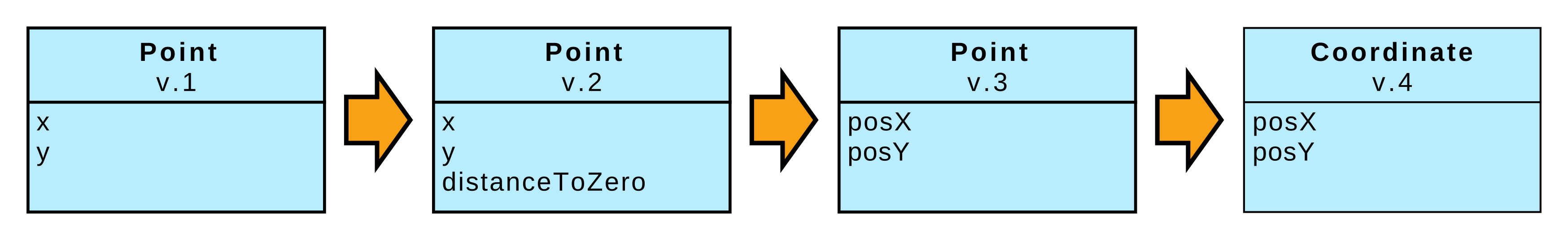

We often need to load objects whose class has changed since it was saved. For example, figure 0.1 illustrates typical changes that can happen to

the class shape. Now imagine we previously serialized an instance of Point and we need to materialize it after Point class has changed.

Let's start with the simple cases. If a variable was inserted, its value will be nil. If it was removed, it is also obvious: the serialized value will be

ignored. The change of Order of instance variables is handled by Fuel automatically.

A more interesting case is when a variable was renamed. Fuel cannot automatically guess the new name of a variable, so the change will be understood by Fuel

as two independent operations: an insertion and a removal. To resolve this problem, the user can tell the Fuel materializer which variables are renamed by

using the message migratedClassNamed:variables:. It takes as first argument the name of the class and as second argument a mapping from old names to new

names. This is illustrated in the following example:

FLMaterializer newDefault

migrateClassNamed: #Point

variables: {'x' -> 'posX'. 'y' -> 'posY'}.

The last change that can happen is a class rename. Again the Fuel

materializer provides a way to handle this: the

migrateClassNamed:toClass: message, and an example of its use is shown below:

FLMaterializer newDefault

migrateClassNamed: #Point

toClass: Coordinate.

Lastly, Fuel defines the message migrateClassNamed:toClass:variables: that combines both class and variable rename.

Additionally, the method globalEnvironment:, shown in Section 3.3, is useful for migration of global variables: you can prepare an ad-hoc environment dictionary with the same keys that were used during serialization, but with the new classes as values.

A class could also change its layout. For example, Point could change from being fixed to variable. Layout changes from fixed to variable format are automatically handled by Fuel. Unfortunately, the inverse (variable to fixed) is not supported yet.

7. Fuel Format Migration

Until now, each Fuel version has used its own stream format, which is not compatible with the format of other versions. This means that when upgrading Fuel, we will need to convert our serialized streams. This is done by using the old version of Fuel to materialize a stream, keeping a reference to this object graph, and then loading the new version of Fuel and serializing the object graph back to a file.

We include below an example of such a format migration. Let's say we have some files serialized with Fuel 1.7 in a Pharo 1.4 image and we want to migrate them to Fuel 1.9.

| oldVersion newVersion fileNames objectsByFileName

materializerClass serializerClass |

oldVersion := '1.7'.

newVersion := '1.9'.

fileNames := #('a.fuel' 'b.fuel' 'c.fuel' 'd.fuel' 'e.fuel').

objectsByFileName := Dictionary new.

(ConfigurationOfFuel project version: oldVersion) load.

"Need to do it like this otherwise

the class is decided at compile time."

materializerClass := Smalltalk at: #FLMaterializer.

fileNames do: [ :fileName |

objectsByFileName

at: fileName

put: (materializerClass materializeFromFileNamed: fileName) ].

(ConfigurationOfFuel project version: newVersion) load.

"Need to do it like this otherwise

the class is decided at compile time."

serializerClass := Smalltalk at: #FLSerializer.

objectsByFileName keysAndValuesDo: [ :fileName :objects |

serializerClass

serialize: objects

toFileNamed: 'migrated-', fileName ].We assume in this example that the number of objects to migrate can be materialized all together at the same time. This assumption may be wrong. In such case, you could adapt the script to split the list of files and do the migration in parts.

This script should be evaluated in the original image. We don't guarantee that Fuel 1.7 loads in Pharo 2.0, but we do know that Fuel 1.9 loads in Pharo 1.4.

8. Built-in Header Support

It can be useful to store additional information with the serialized graph or perform pre and post materialization actions. To achieve this, Fuel supports the possibility to customize the header, an instance of FLHeader.

The following example shows these features: first we add a property called timestamp to the header using the message at:putAdditionalObject:. We then define some pre and post actions using addPreMaterializationAction: and addPostMaterializationAction:, respectively. In the latter we show how we can retrieve the property value by using the additionalObjectAt: message.

| serializer |

serializer := FLSerializer newDefault.

serializer header

at: #timestamp

putAdditionalObject: DateAndTime now rounded.

serializer header

addPreMaterializationAction: [

Transcript show: 'Before serializing'; cr ].

serializer header

addPostMaterializationAction: [ :materialization |

Transcript

show: 'Serialized at ';

show: (materialization additionalObjectAt: #timestamp).

Transcript cr;

show: 'Materialized at ';

show: DateAndTime now rounded;

cr ].

serializer

serialize: 'a big amount of data'

toFileNamed: 'demo.fuel'Then, you can materialize the header info only, and obtain the timestamp property, as follows:

| aHeader |

aHeader := FLMaterializer materializeHeaderFromFileNamed: 'demo.fuel'.

aHeader additionalObjectAt: #timestamp.

If we materialize the whole file, as below, the print string of the results is: 'a big amount of data'.

FLMaterializer materializeFromFileNamed: 'demo.fuel'

And something similar to the following is shown in Transcript:

Before serializing

Serialized at 2015-05-24T22:39:18-03:00

Materialized at 2015-05-24T22:39:37-03:009. Conclusion

Fuel is a fast and stable binary object serializer for Pharo and is available by default in Pharo since 2.0. It can serialize to and materialize from any stream and the graph of objects to be serialized can be customized in multiple ways. It can serialize nearly any object in the system. For example, cases are known of an error occurring in a deployed application, the full stack being serialized and later materialized on a development machine for debugging.