Building and Deploying a Small Web application

This chapter details the whole development process of a Web application in Pharo through a detailed example. Of course, there are an infinite number of ways to make a Web application. Even in Pharo, there are multiple frameworks approaching this problem, most notably Seaside, AIDAweb and Iliad. However, the presented example is directly built on top of the foundational framework called Zinc HTTP Components. By doing so, we'll be touching the fundamentals of HTTP and Web applications and you will understand the actual basic mechanics of building and deploying a Web application.

You will also discover that using nice objects abstracting each concept in HTTP and related open standards makes the actual code easier than you might expect. The dynamic, interactive nature of Pharo combined with its rich IDE and library will allow us to do things that are nearly impossible using other technology stacks. By chronologically following the development process, you will see the app growing from something trivial to the final result. Finally, we will save our source code in a repository and deploy for real in the cloud.

The Web application that we are going to build, shown in Figure 0.1, will display a picture and allow users to change the picture by uploading a new one. Because we want to focus on the basic mechanics, the fundamentals as well as the build and deploy process, there are some simplifications. There will be one picture for all users, no login and we will store the picture in memory.

In our implementation, the route /image will serve an HTML page containing the image and a form. To serve the raw image itself, we'll add a parameter, like

/image?raw=true. These will be GET HTTP requests. The form will submit its data to /image as a POST request.

1. Saying Hello World

Let's lay the groundwork for our new Web application by making a version that only says 'Hello World!'. We'll be extending the Web app gradually until we reach our functional goal.

Open the Nautilus System Browser and create a new package (right click in the first column) called something like 'MyFirstWebApp'.

Now create a new class (right click in the second column) with the same name, MyFirstWebApp.

You will be given a template: edit 'NameOfSubclass' and accept by clicking 'OK'.

Your definition should now appear in the bottom pane.

Object subclass: #MyFirstWebApp

instanceVariableNames: ''

classVariableNames: ''

poolDictionaries: ''

category: 'MyFirstWebApp'

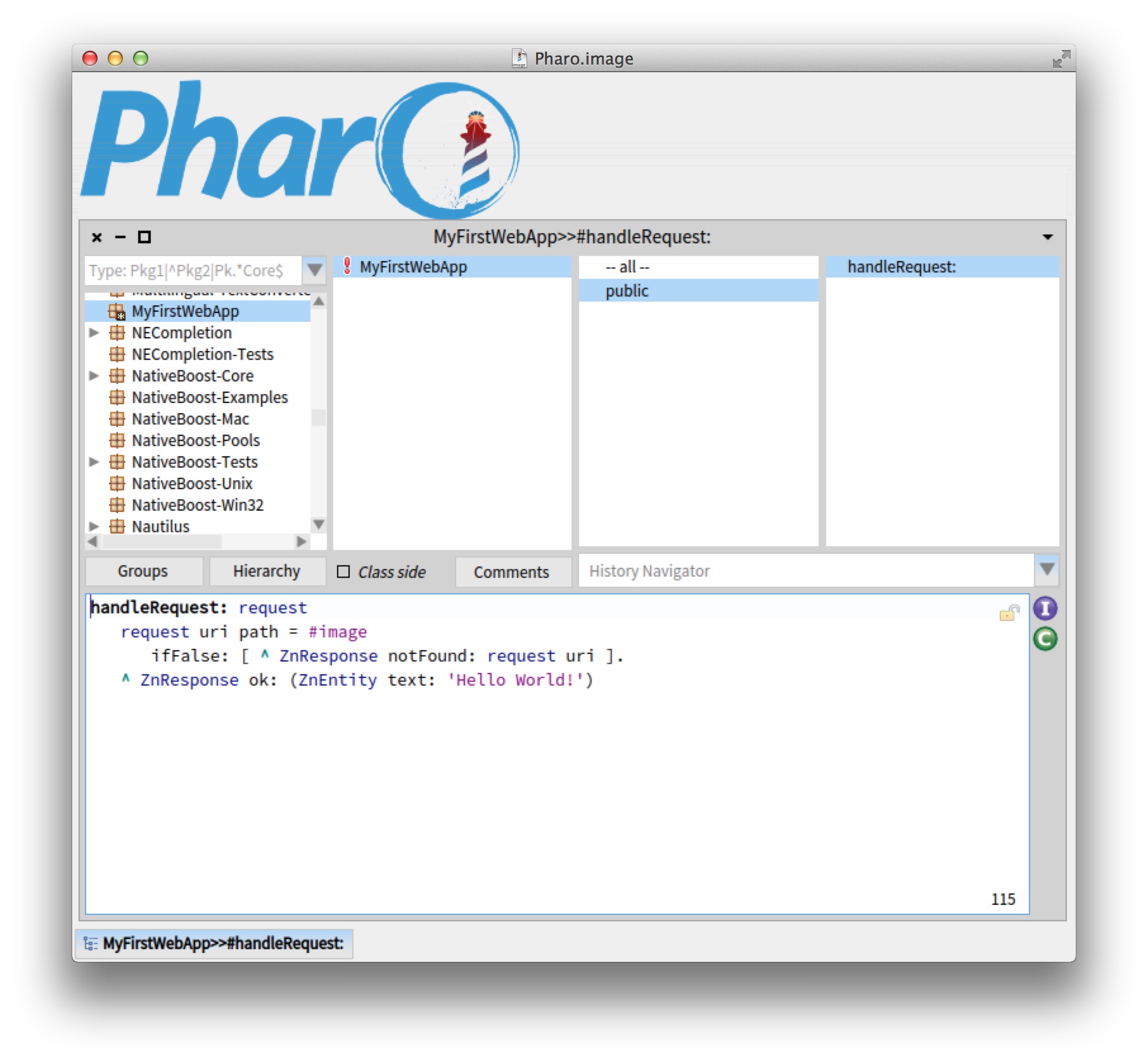

Any object can be a Web app, it only has to respond to the

handleRequest: message to answer a response based on a request. Now add the following method:

MyFirstWebApp>>handleRequest: request

request uri path = #image

ifFalse: [ ^ ZnResponse notFound: request uri ].

^ ZnResponse ok: (ZnEntity text: 'Hello World!')

Create a new protocol called public (by right-clicking in the third column). When the new protocol is selected, a new method template will appear in the bottom

pane. Overwrite the whole template with the code above and accept it as shown Figure 0.2.

What we do here is to look at the incoming request to make sure the URI path is /image which will be the final name of our Web app.

If not, we return a Not Found (code 404) response.

If so, we create and return an OK response (code 200) with a simple text entity as body or payload.

Now we define the method value: to make it an alias of handleRequest: as follows:

MyFirstWebApp>>value: request

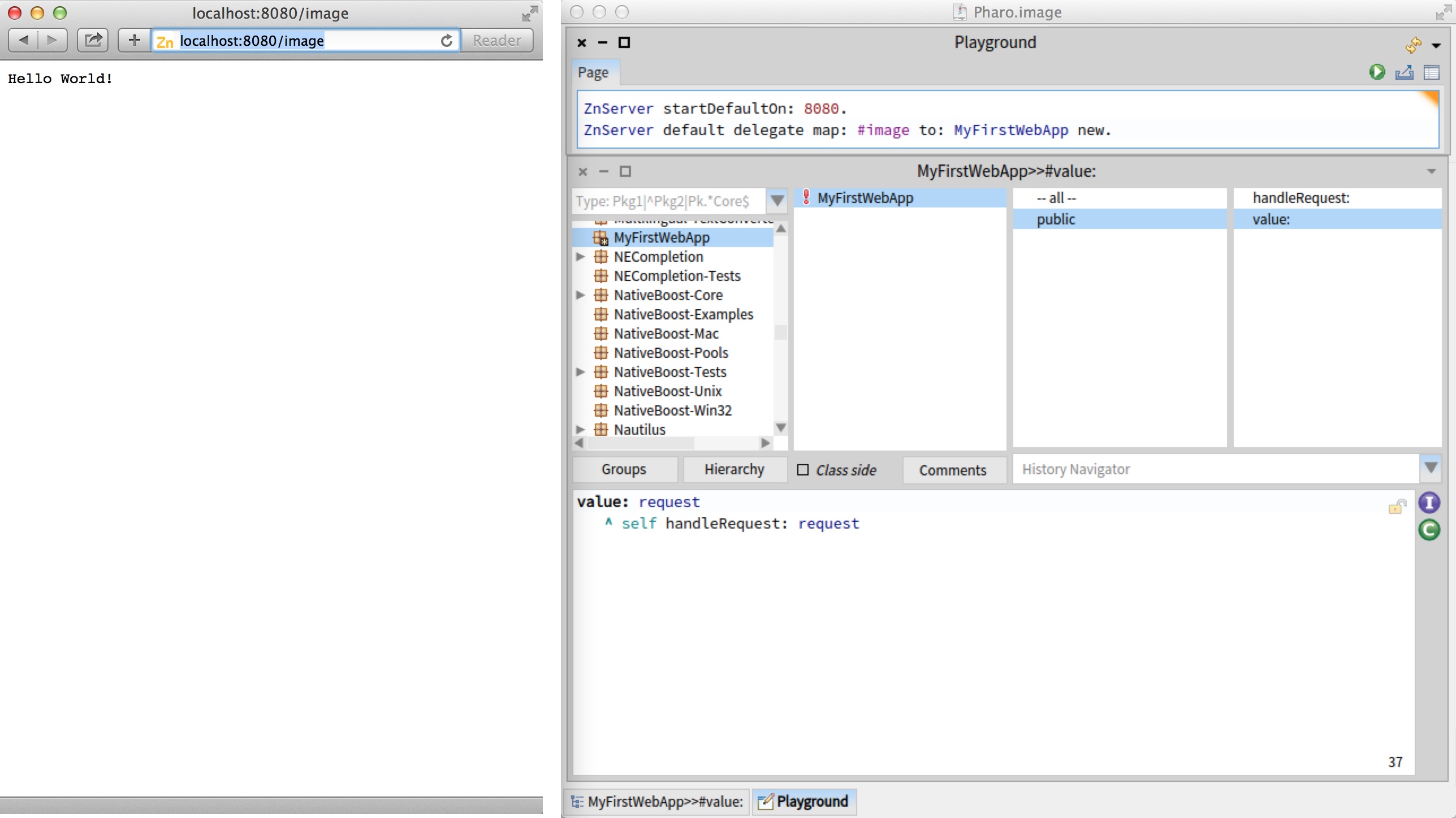

^ self handleRequest: requestThis is needed so our Web app object can be used more flexibly. To test our Web app, we'll add it as one of the pages of the default server, like this:

ZnServer startDefaultOn: 8080.

ZnServer default delegate map: #image to: MyFirstWebApp new.

The second expression adds a route from /image to an

MyFirstWebApp instance.

If all is well, http://localhost:8080/image should show a friendly message as shown in Figure 0.3.

Note how we are not even serving HTML, just plain text.

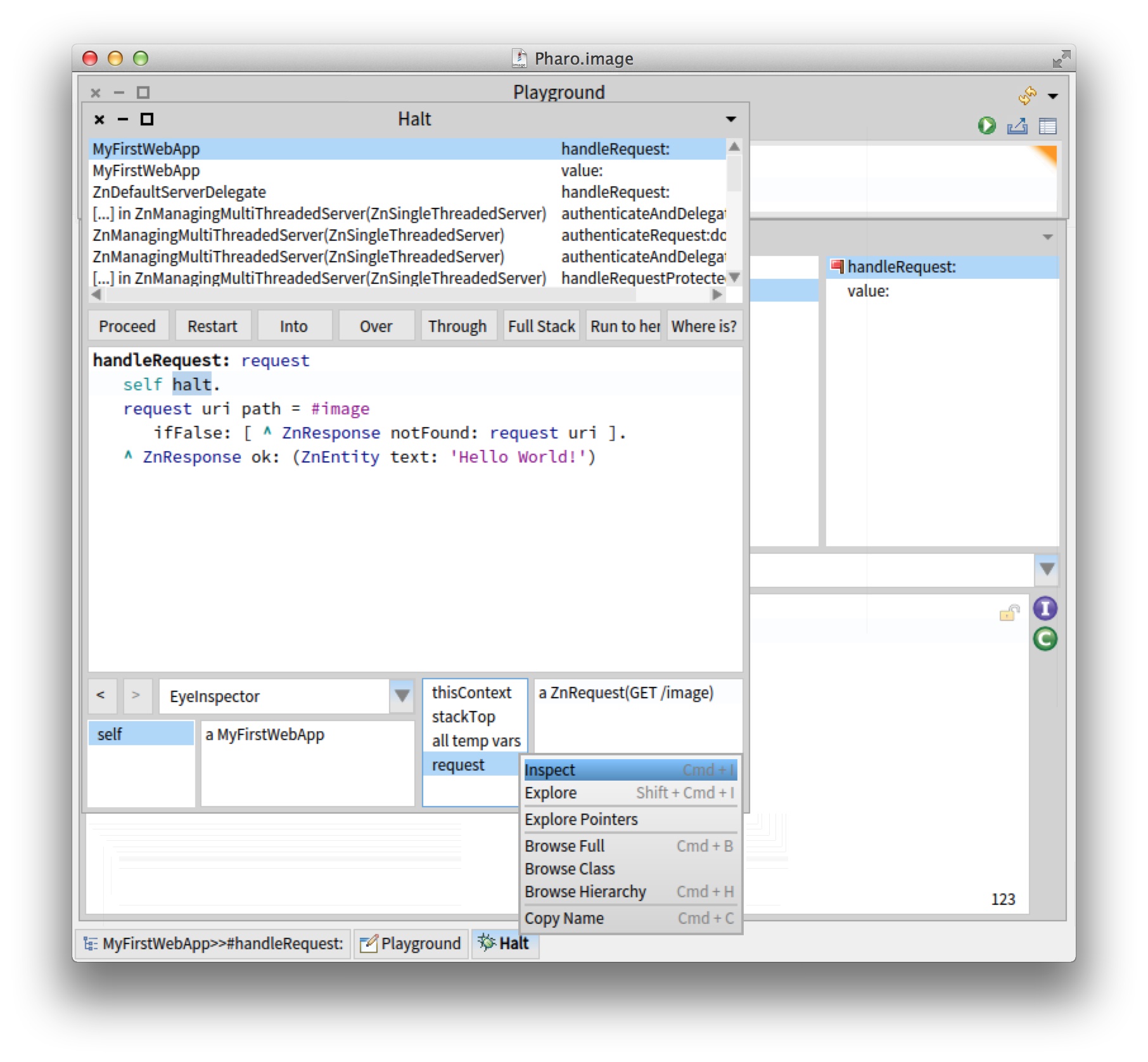

1.1. Debugging our Web App

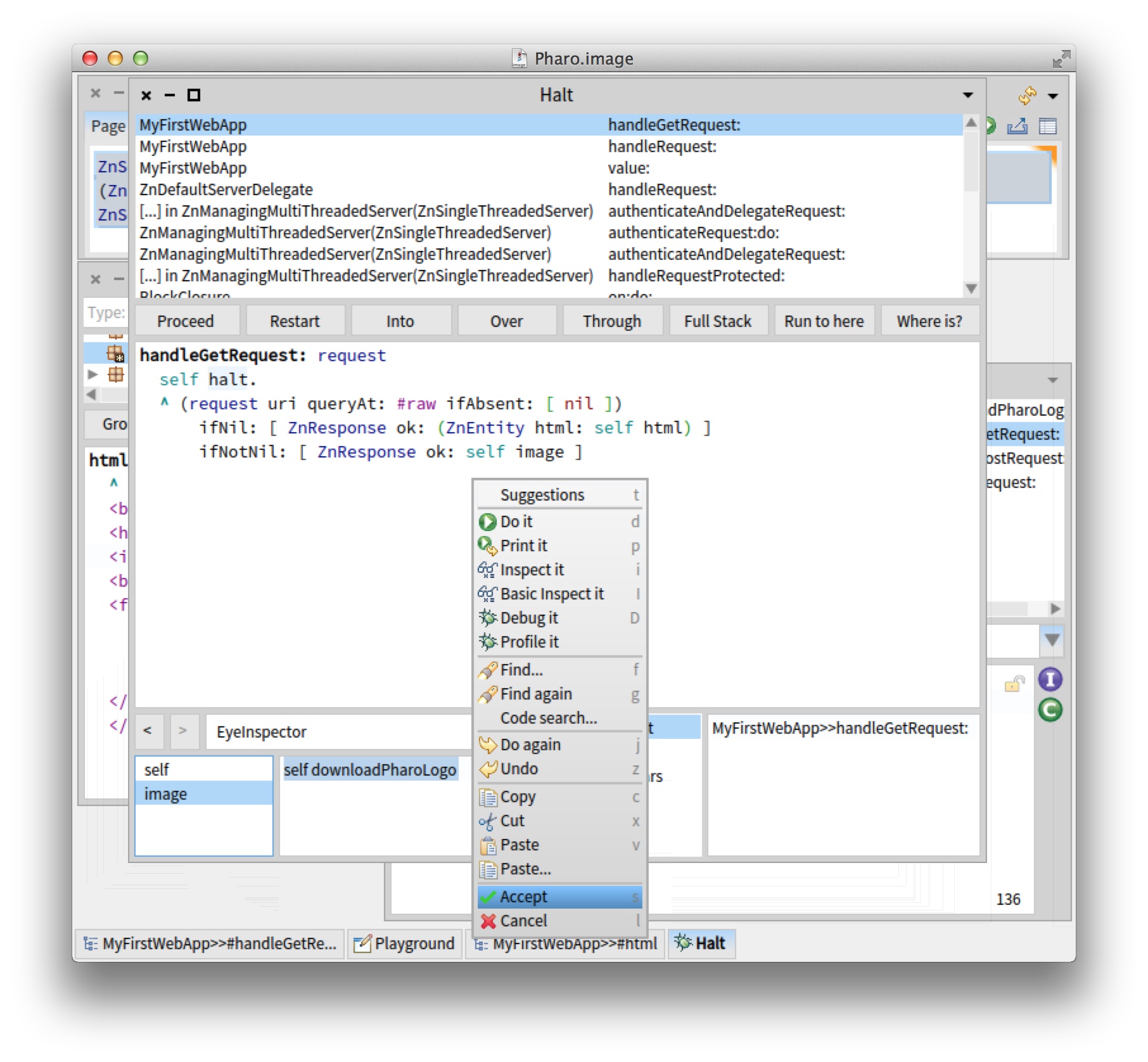

Try putting a breakpoint in MyFirstWebApp>>handleRequest: (by inserting self halt in the method source code).

Then, if you refresh the page from the web browser, a debugger will open in Pharo allowing you to inspect things.

You can just continue the execution by clicking on the proceed button.

Or you can look into the actual request and response objects as shown in Figure 0.4.

Note how Pharo is a live environment: you can change the behavior of the application in the debugger window (such as changing the response's text) and the change is immediately used.

You can leave the server running. If you want you can enable logging, or switch to debug mode and inspect the server instance as explained in Chapter Zinc Server. Don't forget to remove any breakpoints you set before continuing.

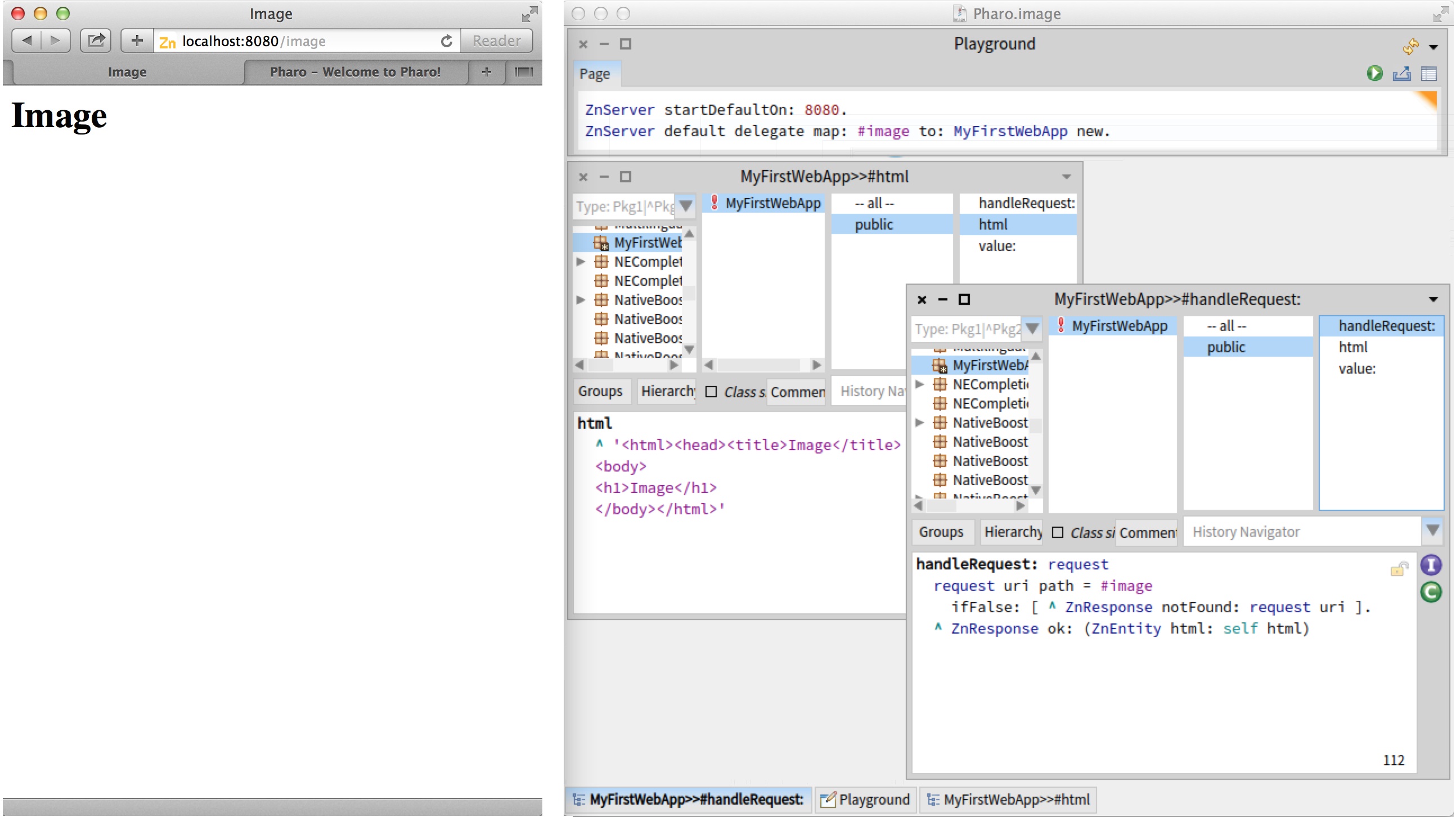

2. Serving an HTML Page With an Image

HTML generation can be done with some of existing high-level Pharo frameworks such as Mustache (see Chapter Mustache).

In the following, we manually compose the HTML to focus on app building and deployment.

Go ahead and add a new method named html.

MyFirstWebApp>>html

^ '<html><head><title>Image</title>

<body>

<h1>Image</h1>

</body></html>'

Additionally, change the handleRequest: method to use the new method.

MyFirstWebApp>>handleRequest: request

request uri path = #image

ifFalse: [ ^ ZnResponse notFound: request uri ].

^ ZnResponse ok: (ZnEntity html: self html)Refresh the page in your web browser. You should now see an HTML page as in Figure 0.5.

You have probably noted the red exclamation mark icon in front of our class name in the browser.

This is an indication that we have no class comment, which is not good: documentation is important.

Click the Comments button and write some documentation.

You can also use the class comment as a notepad for yourself, saving useful expressions that you can later execute in place such as the two expressions above to start the server.

2.1. Serving an Image

For the purpose of our Web app, images can be any of three types: GIF, JPEG and PNG. The application will store them in memory as an object wrapping the actual bytes together with a MIME type.

To simplify our app, we will arrange things so that we always start with a default image, then we always have something to show. Let's add a little helper: the downloadPharoLogo method:

MyFirstWebApp>>downloadPharoLogo

^ ZnClient new

beOneShot;

get: 'http://pharo.org/files/pharo.png';

entity

Quickly test the code by selecting the method body (not including the name) and inspecting the result.

You should get the bytes of an image back.

Now add the accessor image defined as follow:

MyFirstWebApp>>image

^ image ifNil: [ image := self downloadPharoLogo ]

When you try to accept this method, you will get an error.

The method is trying to use an unknown variable named image.

Select the option to automatically declare a new instance variable.

Remember that we decided we were going to serve the raw image itself using a query variable, like /image?raw=true.

Make the following modification to existing methods and add a new one as shown below.

MyFirstWebApp>>html

^ '<html><head><title>Image</title>

<body>

<h1>Image</h1>

<img src="image?raw=true"/>

</body></html>'

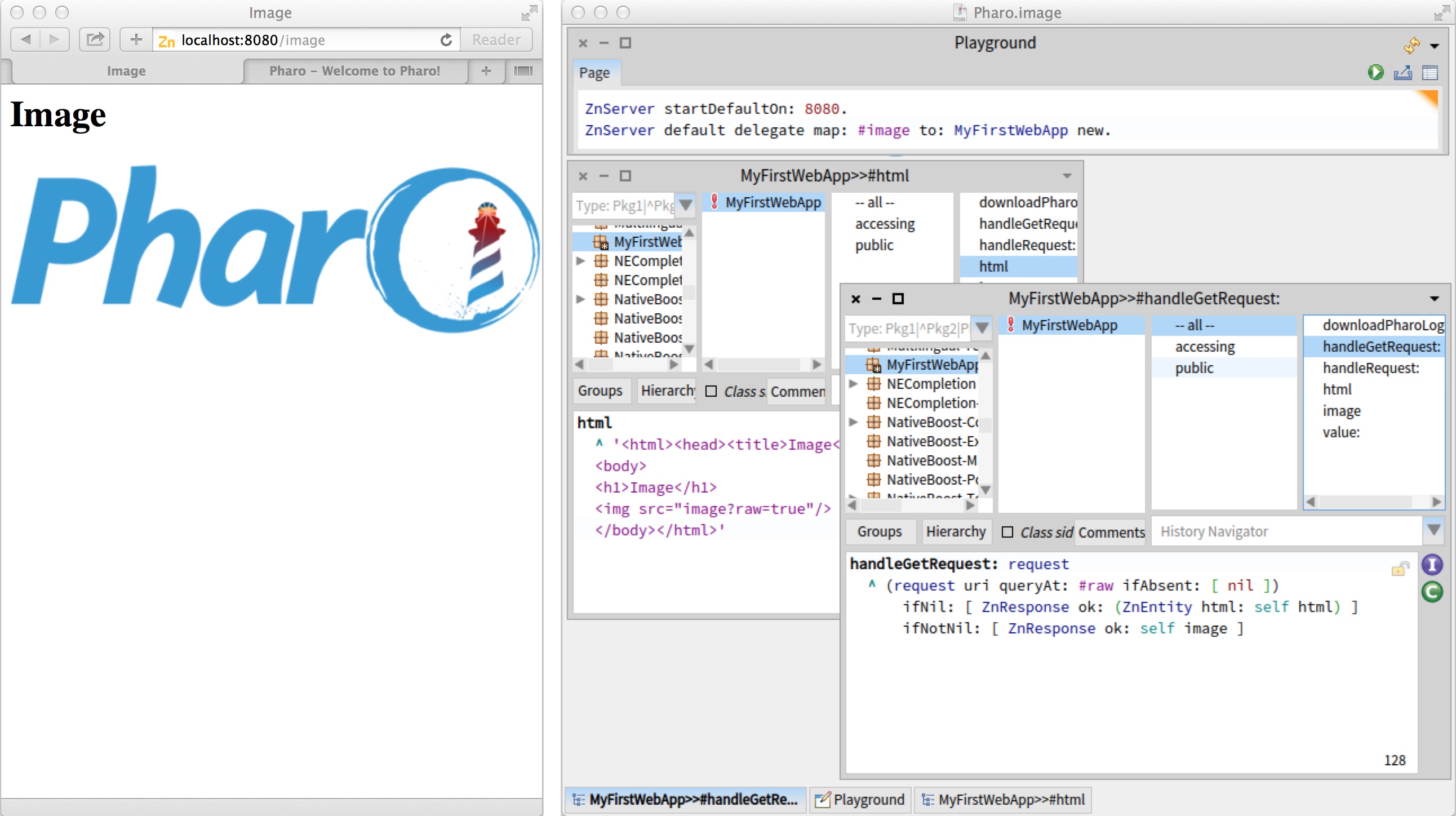

MyFirstWebApp>>handleRequest: request

request uri path = #image

ifFalse: [ ^ ZnResponse notFound: request uri ].

^ self handleGetRequest: request

MyFirstWebApp>>handleGetRequest: request

^ (request uri queryAt: #raw ifAbsent: [ nil ])

ifNil: [ ZnResponse ok: (ZnEntity html: self html) ]

ifNotNil: [ ZnResponse ok: self image ]

The HTML code now contains an img element. The handleRequest: method now delegates the response generation to a dedicated handleGetRequest: method. This method inspects the incoming URI.

If the URI has a non-empty query variable raw, we serve the raw image directly. Otherwise, we serve the HTML page like before.

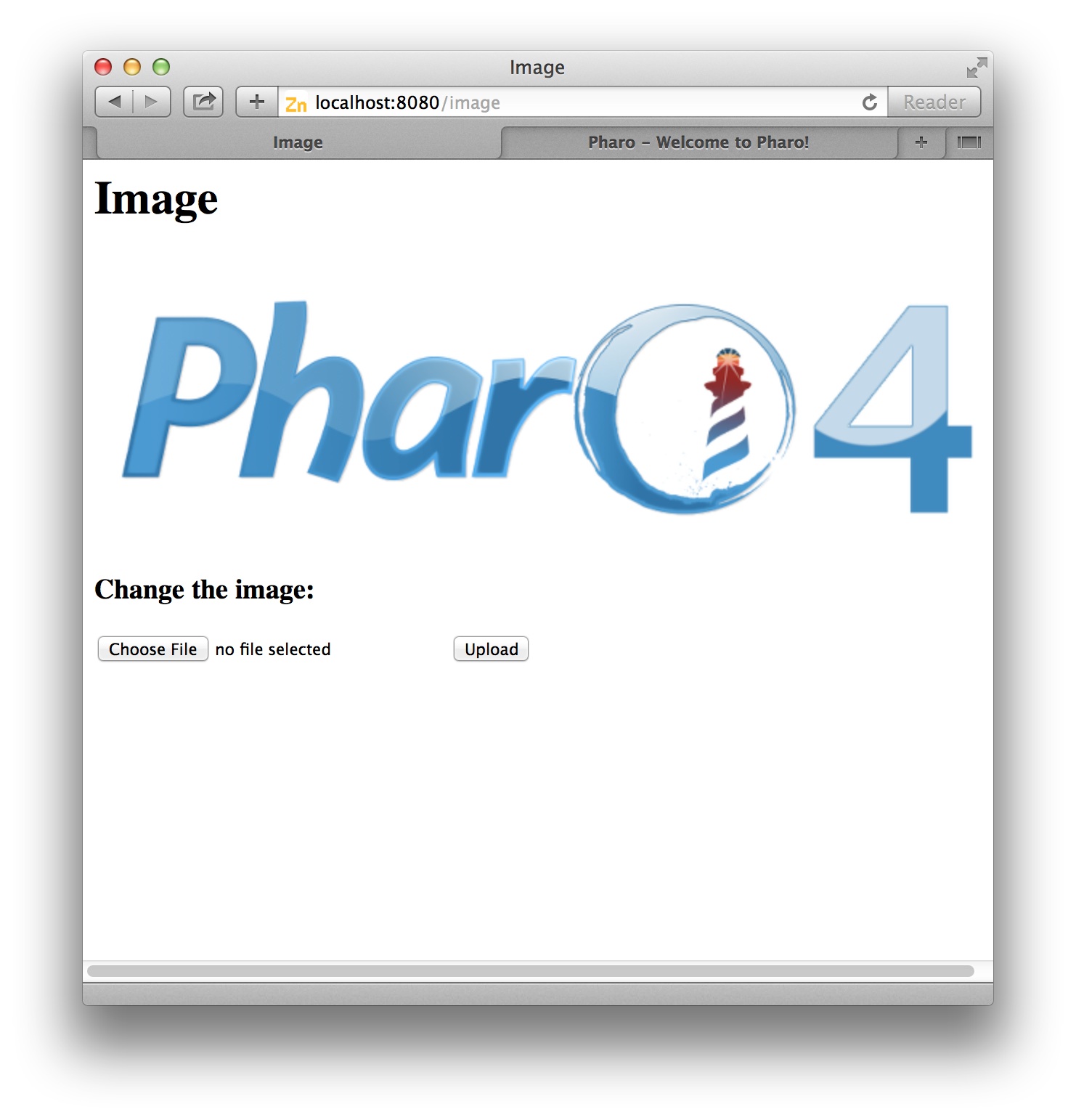

When you refresh the page in the web browser, you should now see an image as in Figure 0.6.

3. Allowing Users to Upload an Image

Interaction is what differentiates a Web site from a Web application. We will now add the ability for users to upload a new image to change the one on the server. To add this ability we need to use an HTML form. Let's change our HTML one last time.

MyFirstWebApp>>html

^ '<html><head><title>Image</title>

<body>

<h1>Image</h1>

<img src="image?raw=true"/>

<br/>

<form enctype="multipart/form-data" action="image" method="POST">

<h3>Change the image:</h3>

<input type="file" name="file"/>

<input type="submit" value= "Upload"/>

</form> </body> </html>'

The user will be able to select a file on the local disk for upload.

When he clicks on the Upload submit button, the web browser will send an HTTP POST request to the action URL, /image, encoding the form contents using a technique called multi-part form-data.

With the above change, you will see the form but nothing will happen if you click the submit button: this is because the server does not know how to process the incoming form data.

In our request handling, we have to distinguish between GET and POST requests.

Change handleRequest: one last time:

MyFirstWebApp>>handleRequest: request

request uri path = #image ifTrue: [

request method = #GET ifTrue: [

^ self handleGetRequest: request ].

request method = #POST ifTrue: [

^ self handlePostRequest: request ] ].

^ ZnResponse notFound: request uri

Now we have to add an implementation of handlePostRequest: to accept the uploaded image and change the current one.

MyFirstWebApp>>handlePostRequest: request

| part |

part := request entity partNamed: #file.

image := part entity.

^ ZnResponse redirect: #imageWe start with a simple version without error handling. The entity of the incoming request is a multi-part form-data object containing named parts. Each part, such as the file part, contains another sub-entity: in our case, the uploaded image. Note how the response to the POST is a redirect to the main page. You should now have a fully functional web application.

Nevertheless, we have taken a bit of a shortcut in the code above. It is pretty dangerous to just accept what is coming in from the internet without doing any checking. Here is an improved version.

MyFirstWebApp>>handlePostRequest: request

| part newImage badRequest |

badRequest := [ ^ ZnResponse badRequest: request ].

request hasEntity ifFalse: badRequest.

(request contentType matches: ZnMimeType multiPartFormData)

ifFalse: badRequest.

part := request entity

partNamed: #file

ifNone: badRequest.

newImage := part entity.

(newImage notNil

and: [ newImage contentType matches: 'image/*' asZnMimeType ])

ifFalse: badRequest.

image := newImage.

^ ZnResponse redirect: #image

Our standard response when something is wrong will be to return a Bad Request (code 400).

We define this behavior in a temporary variable so that we can reuse it multiple times over.

The first test makes sure the current POST request actually contains an entity and that it is of the correct type.

Next, the code checks that there is no file part.

Finally, the code makes sure the file part is actually an image by matching with the wildcard image/* MIME type. The user can now upload a new image through the application as can be seen in Figure 0.7. This image is saved in memory and displayed for all visitors until the application is restarted.

If you are curious, set a breakpoint in the handlePostRequest: method and inspect the request object of an actual request.

You will learn a lot from inspecting and manipulating live objects.

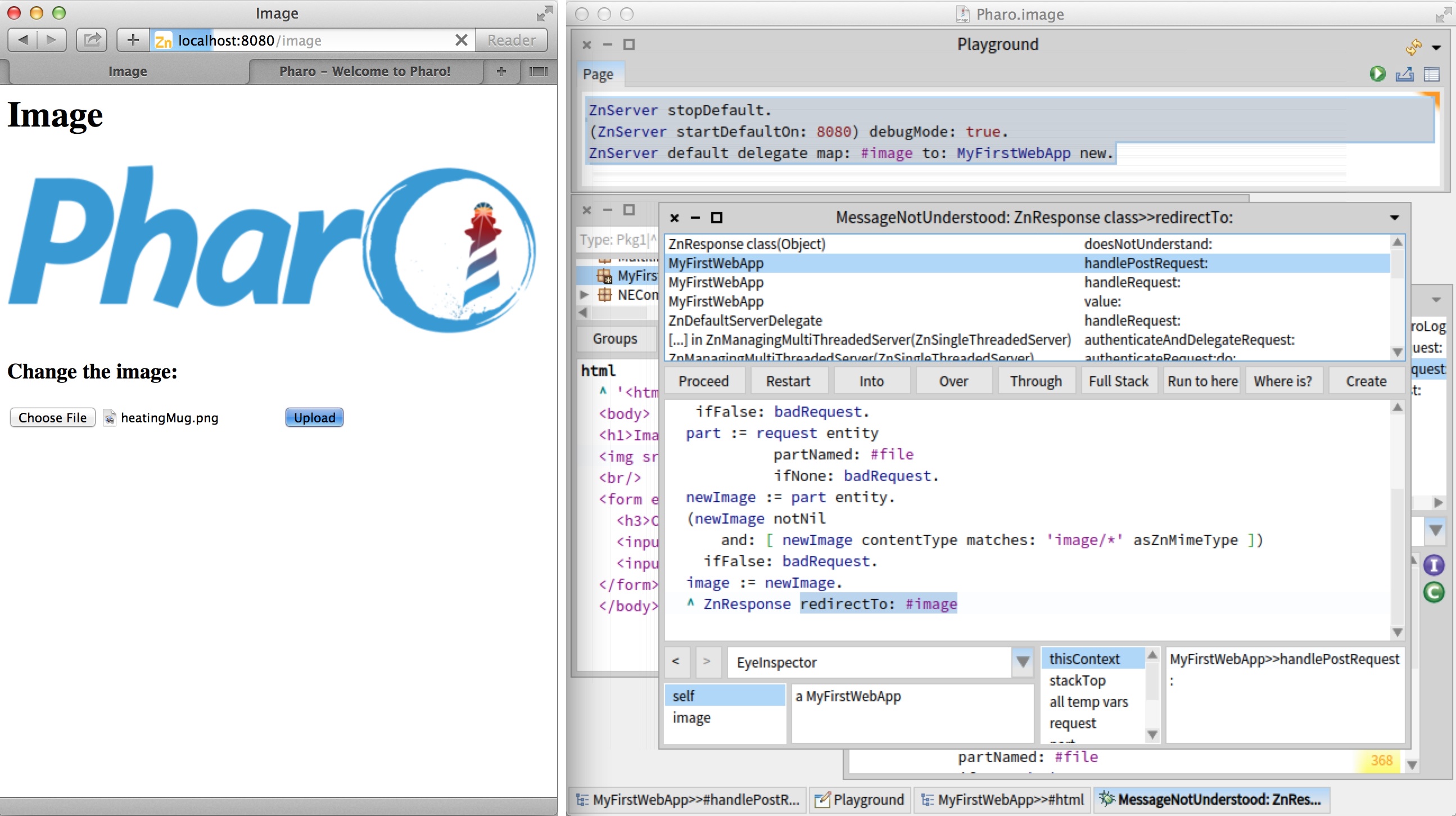

4. Live Debugging

Let's make a deliberate error in our code.

Change handlePostRequest: so that the last line reads like:

^ ZnResponse redirectTo: #imageThe compiler will already complain, ignore the warning and accept the code anyway. If you try to upload a new image, your browser window will display a following text which corresponds to a Pharo error:

MessageNotUnderstood: ZnResponse class>>redirectTo:But, we can do better and activate the debug mode of the server. Let's stop and restart our Web app using:

ZnServer stopDefault.

(ZnServer startDefaultOn: 8080) debugMode: true.

ZnServer default delegate map: #image to: MyFirstWebApp new.

If you now try to upload an image through the Web browser, the debugger will pop up in Pharo telling you that ZnResponse does not understand redirectTo: and show you the offending code. You could fix the code and try uploading again to see if it works as shown in Figure 0.8.

But we can do even better! Just fix the code directly within the debugger window and accept it. Now you can restart and proceed the execution. The same request is still active and the server will now do the correct thing. Have a look at your Web browser: you will see that your initial action, the upload, that first initially hung, has now succeeded.

Up to now, the suggestion was that you can use the debugger and inspector tools to look at requests and responses.

But you can actually change them while they are happening!

Prepare for our experiment by making sure that you change the image to be different from the default one.

Now set a breakpoint in handleGetRequest: and reload the main page.

There will be two requests coming in: the first request for /image and the second request for /image?raw=true.

Proceed the first one.

Now, with the execution being stopped for the second request, click on the image instance variable in the bottom left pane (see Figure 0.9). The pane next to it will show some

image entity. Select the whole contents and replace it with self downloadPharoLogo and accept the change. Now proceed the execution. Your previously

uploaded image is gone, replaced again by the default Pharo logo. We just changed an object in the middle of the execution. Imagine doing all your development

like that, having a real conversation with your application, while you are developing it. Be warned though: once you get used to this, it will be hard to go back.

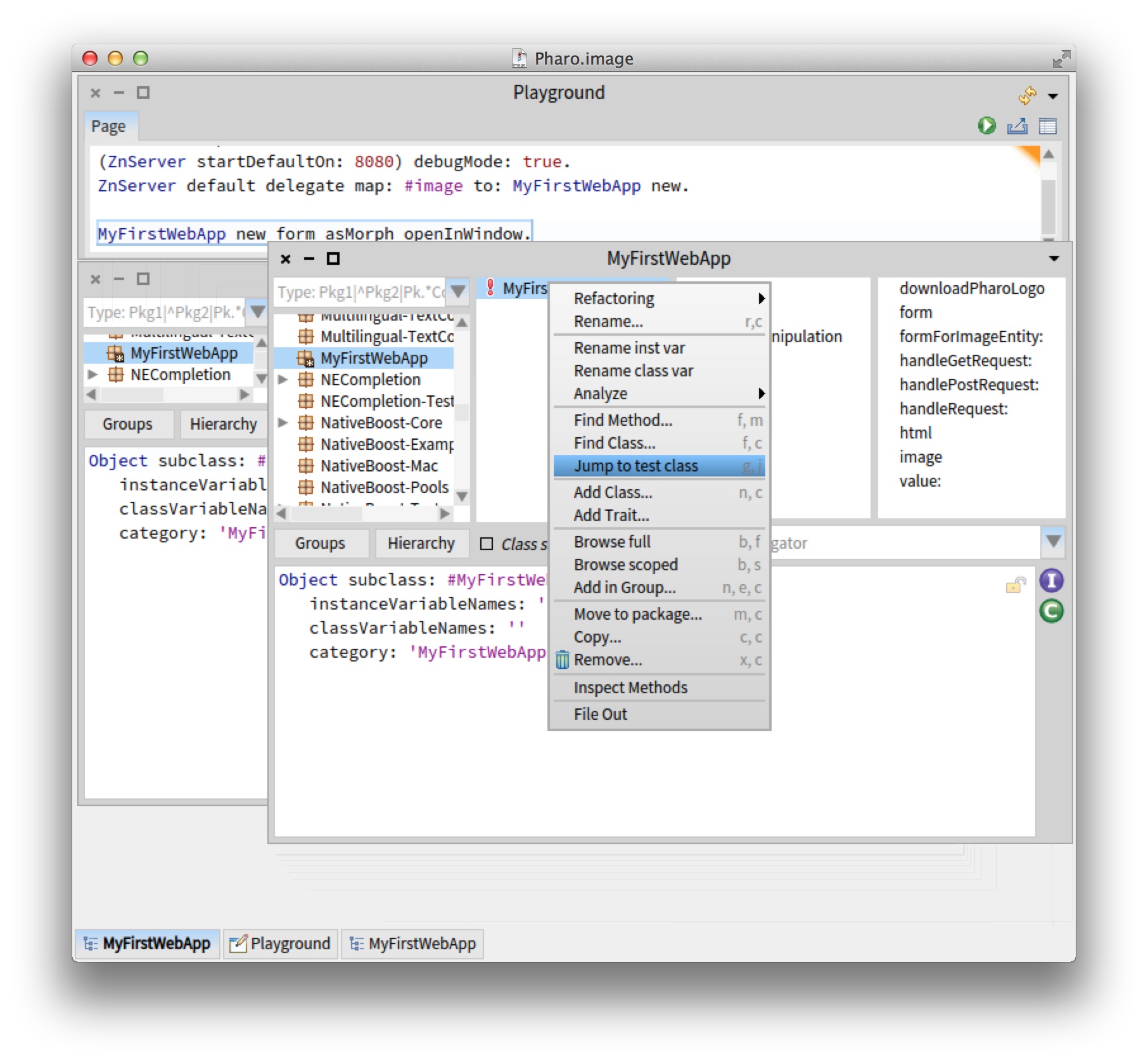

5. Image Magic

The abilities to look at the requests and responses coming in and going out of the server, to set breakpoints, to debug live request without redoing the user interaction or to modify data structure live are already great and quite unique. But there is more. Pharo is not just a platform for server applications, it can be used to build regular applications with normal graphics as well. In fact, it is very good at it. That is why it has built-in support to work with JPEG, GIF or PNG.

Would it not be cool to be able to actually parse the image that we were manipulating as an opaque collection of bytes up till now? To make sure it is real. To look at it while debugging. Turns out this is quite easy. Are you ready for some image magick, pun intended?

The Pharo object that represents images is called a form. There are objects called GIFReadWriter, PNGReadWriter and JPEGReadWriter that can parse

bytes into forms. Add two helper methods, formForImageEntity: and form.

MyFirstWebApp>>formForImageEntity: imageEntity

| imageType parserClassName parserClass parser |

imageType := imageEntity contentType sub.

parserClassName := imageType asUppercase, #ReadWriter.

parserClass := Smalltalk globals at: parserClassName asSymbol.

parser := parserClass on: imageEntity readStream.

^ parser nextImage

MyFirstWebApp>>form

^ self formForImageEntity: self image

What we do is use the sub type of the mime type, like "png" in image/png, to find the parser class. Then we instantiate a new parser on a read stream on the

actual bytes and invoke the parser with sending nextImage, which will return a form. The form method makes it easy to invoke all this logic on our current image.

Now we can have a look at, for example, the default image like this:

MyFirstWebApp new form asMorph openInWindow.

Obviously you can do this while debugging too. We can also use the image parsing logic to improve our error checking even further. Here is the final version of handlePostRequest:

MyFirstWebApp>>handlePostRequest: request

| part newImage badRequest |

badRequest := [ ^ ZnResponse badRequest: request ].

(request hasEntity

and: [ request contentType matches: ZnMimeType multiPartFormData ])

ifFalse: badRequest.

part := request entity

partNamed: #file

ifNone: badRequest.

newImage := part entity.

(newImage notNil

and: [ newImage contentType matches: 'image/*' asZnMimeType ])

ifFalse: badRequest.

[ self formForImageEntity: newImage ]

on: Error

do: badRequest.

image := newImage.

^ ZnResponse redirect: #imageBefore making the actual assignment of the new image to our instance variable we added an extra expression. We try parsing the image. We are not interested in the result, but we do want to reply with a bad request when the parsing has failed.

Once we have a form object, the possibilities are almost endless. You can query a form for its size, depth and other elements. You can manipulate the form in various ways: scaling, resizing, rotating, flipping, cropping, compositing. And you can do all this in an interactive and dynamic environment.

6. Adding Tests

We all know that testing is good, but how do we actually test a Web app? Writing some basic tests is actually not difficult, since Zinc HTTP Components covers both the client and the server side with the same objects.

Writing tests is creating objects, letting them interact and asserting some conditions.

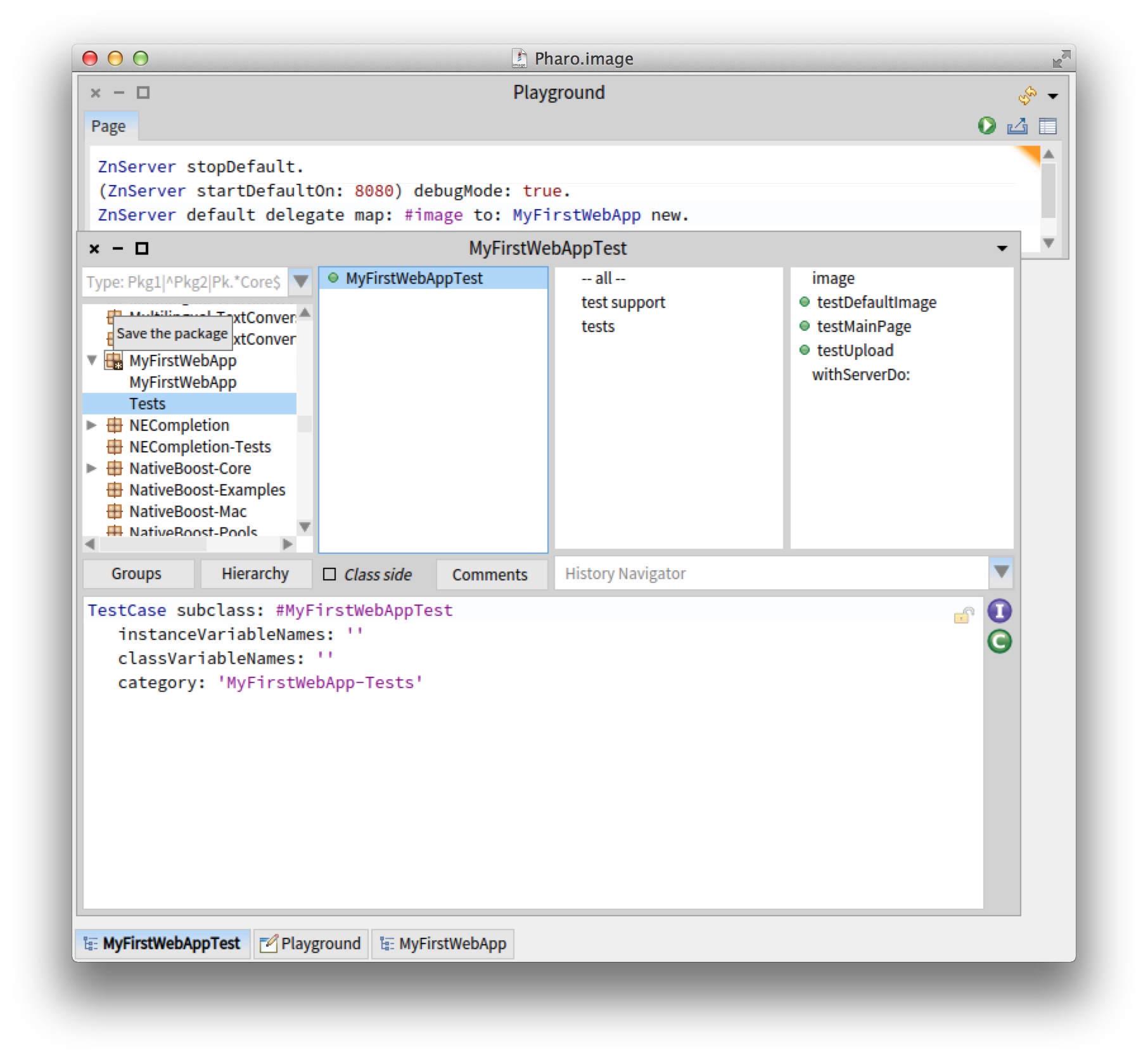

Start by creating a new subclass MyFirstWebAppTest of TestCase.

The Pharo browser helps you here using the "Jump to test class" item in the contextual menu on MyFirstWebApp (see Figure 0.10).

Add now the following helper method on MyFirstWebAppTest:

MyFirstWebAppTest>>withServerDo: block

| server |

server := ZnServer on: 1700 + 10 atRandom.

[

server start.

self assert: server isRunning & server isListening.

server delegate: MyFirstWebApp new.

block cull: server

] ensure: [ server stop ]

Since we will need a configured server instance with our Web app as delegate for each of our tests, we move that logic into #withServerDo: and make sure the server is OK and properly stopped afterwards.

Now we are ready for our first test.

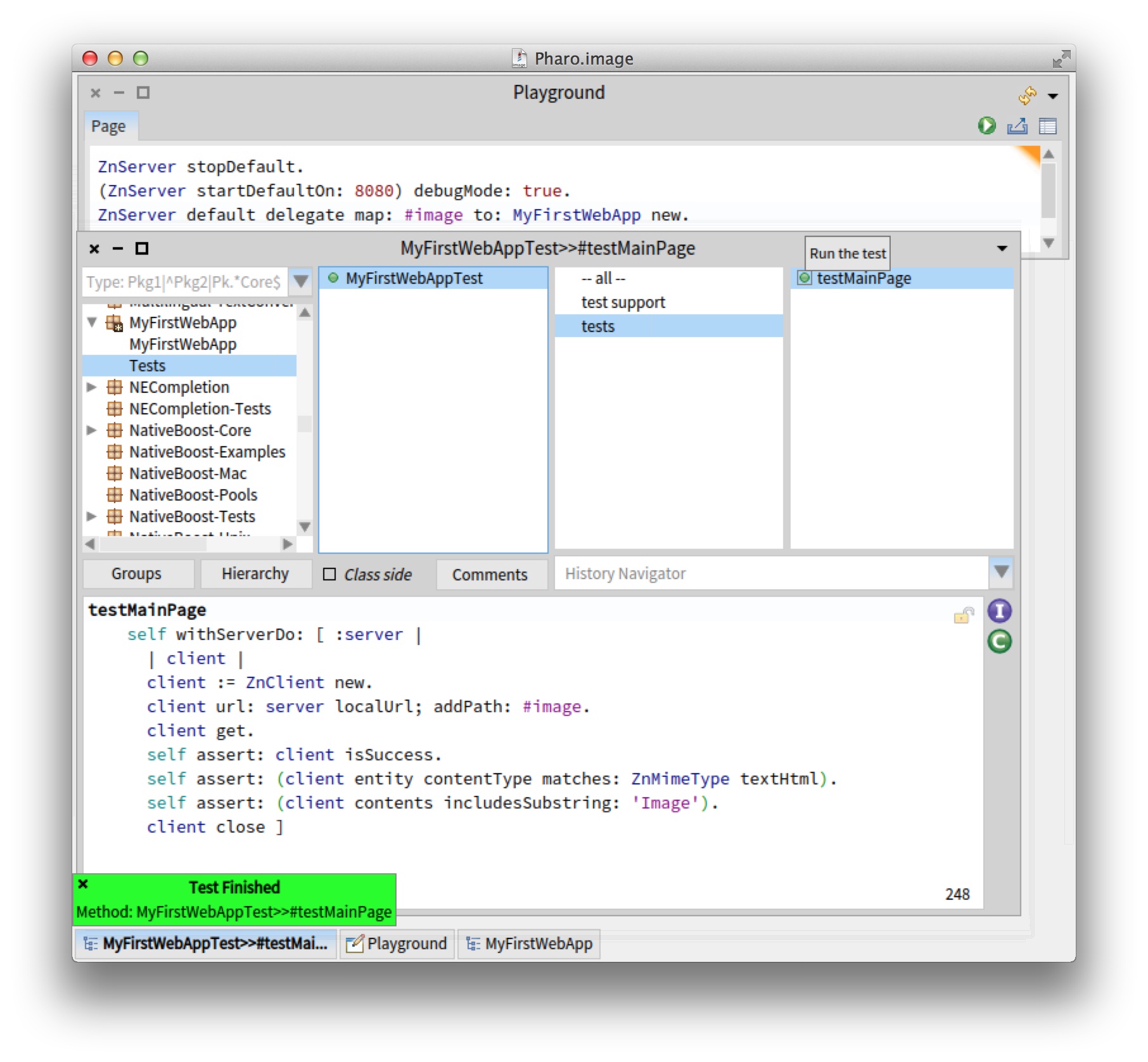

MyFirstWebAppTest>>testMainPage

self withServerDo: [ :server |

| client |

client := ZnClient new.

client url: server localUrl; addPath: #image.

client get.

self assert: client isSuccess.

self assert: (client entity contentType matches: ZnMimeType textHtml).

self assert: (client contents includesSubstring: 'Image').

client close ]

In testMainPage we do a request for the main page, /image, and assert that the request is successful and contains HTML. Make sure the test is green by running it from the system browser by clicking on the round icon in front of the method name in the fourth pane (see Figure 0.11).

Let's try to write a test for the actual raw image being served.

MyFirstWebAppTest>>testDefaultImage

self withServerDo: [ :server |

| client |

client := ZnClient new.

client url: server localUrl; addPath: #image; queryAt: #raw put: #true.

client get.

self assert: client isSuccess.

self assert: (client entity contentType matches: 'image/*' asZnMimeType).

self assert: client entity equals: server delegate image.

client close ]Note how we can actually test for equality between the served image and the one inside our app object (the delegate). Run the test.

Our final test will actually do an image upload and check if the served image did actually change to what we uploaded. Here we define the method image that

returns a new image.

MyFirstWebAppTest>>image

^ ZnClient new

beOneShot;

get: 'http://zn.stfx.eu/zn/Hot-Air-Balloon.gif';

entity

MyFirstWebAppTest>>testUpload

self withServerDo: [ :server |

| image client |

image := self image.

client := ZnClient new.

client url: server localUrl; addPath: #image.

client addPart: (ZnMimePart fieldName: #file entity: image).

client post.

self assert: client isSuccess.

client resetEntity; queryAt: #raw put: #true.

client get.

self assert: client isSuccess.

self assert: client entity equals: image.

client close ]The HTTP client object is pretty powerful. It can do a correct multi-part form-data POST, just like a browser. Furthermore, once configured, it can be reused, like for the second GET request.

7. Saving Code to a Repository

If all is well, you now have a package called MyFirstWebApp containing two classes, MyFirstWebApp and MyFirstWebAppTest. The first one should have

9 methods, the second 5. If you are unsure about your code, you can double check with the full listing at the end of this document. Our Web app should now work

as expected, and we have some tests to prove it.

But our code currently only lives in our development image. Let's change that and move our code to a source code repository.

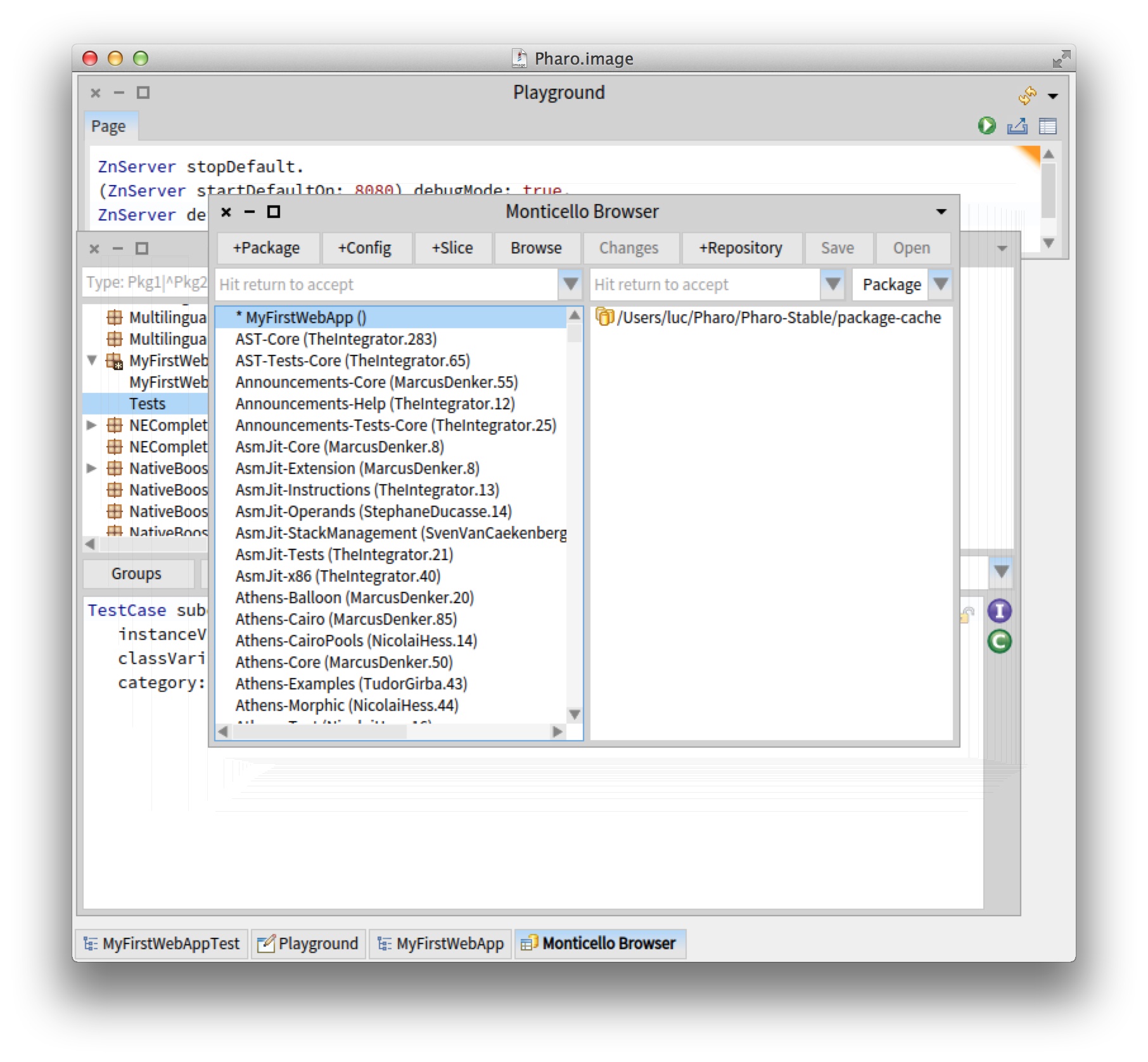

7.1. The Monticello Browser

For this we first have to use the Monticello Browser tool.

In the first pane of the Nautilus Browser, click on the icon in front of your package named MyFirstWebApp as shown in Figure 0.12.

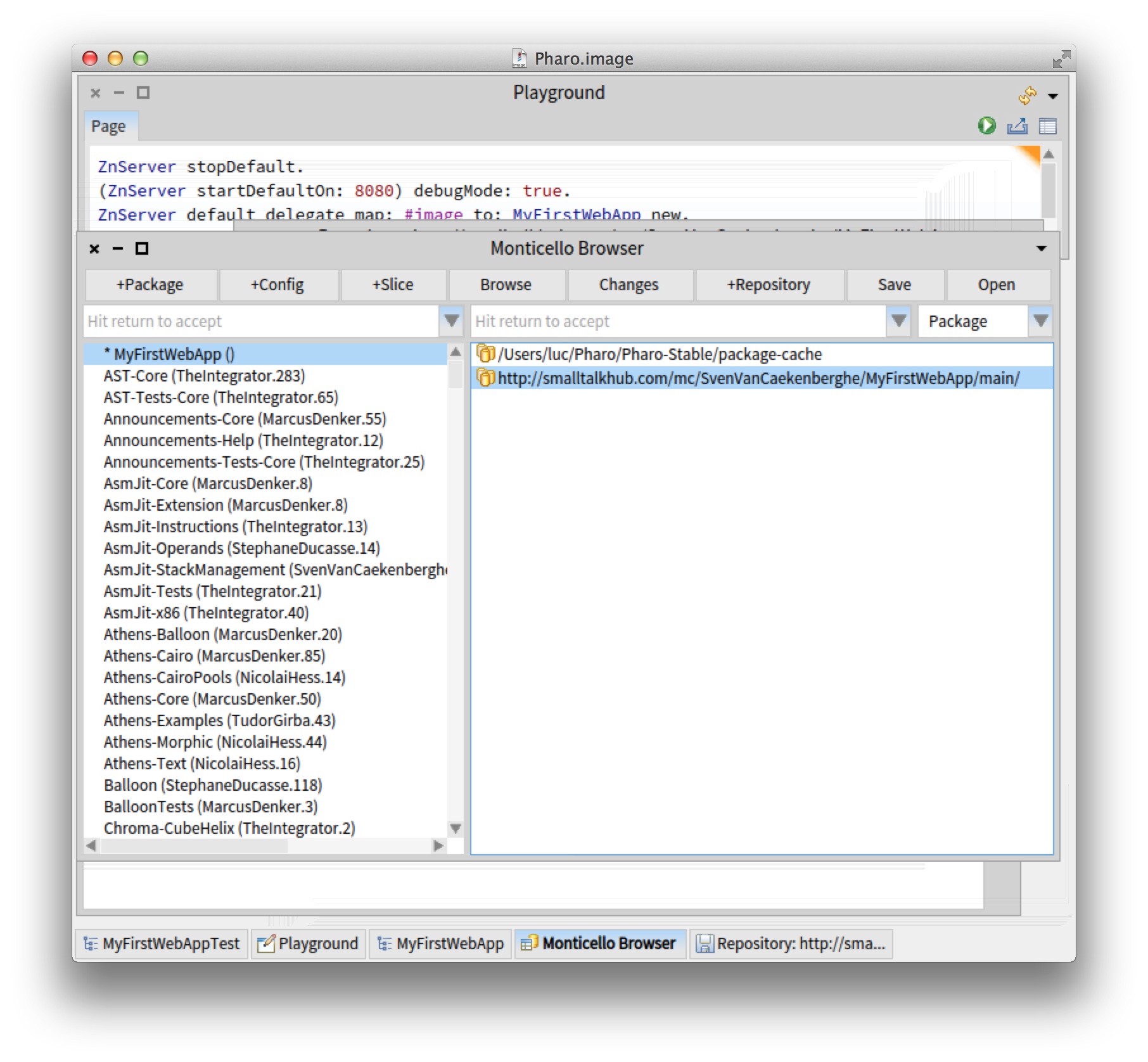

Once opened, Monticello shows on it left pane the list of loaded packages. The currently selected one should be yours as depicted in Figure 0.13.

The left pane of Monticello shows the list of repositories in which the currently selected package can be saved.

Indeed, Pharo uses distributed source code management.

Your code can live on your local file system, or it can live on a server.

As shown in Figure 0.13, by default, your MyFirstWebApp package can only be saved locally in a directory.

We can easily add a remote repository.

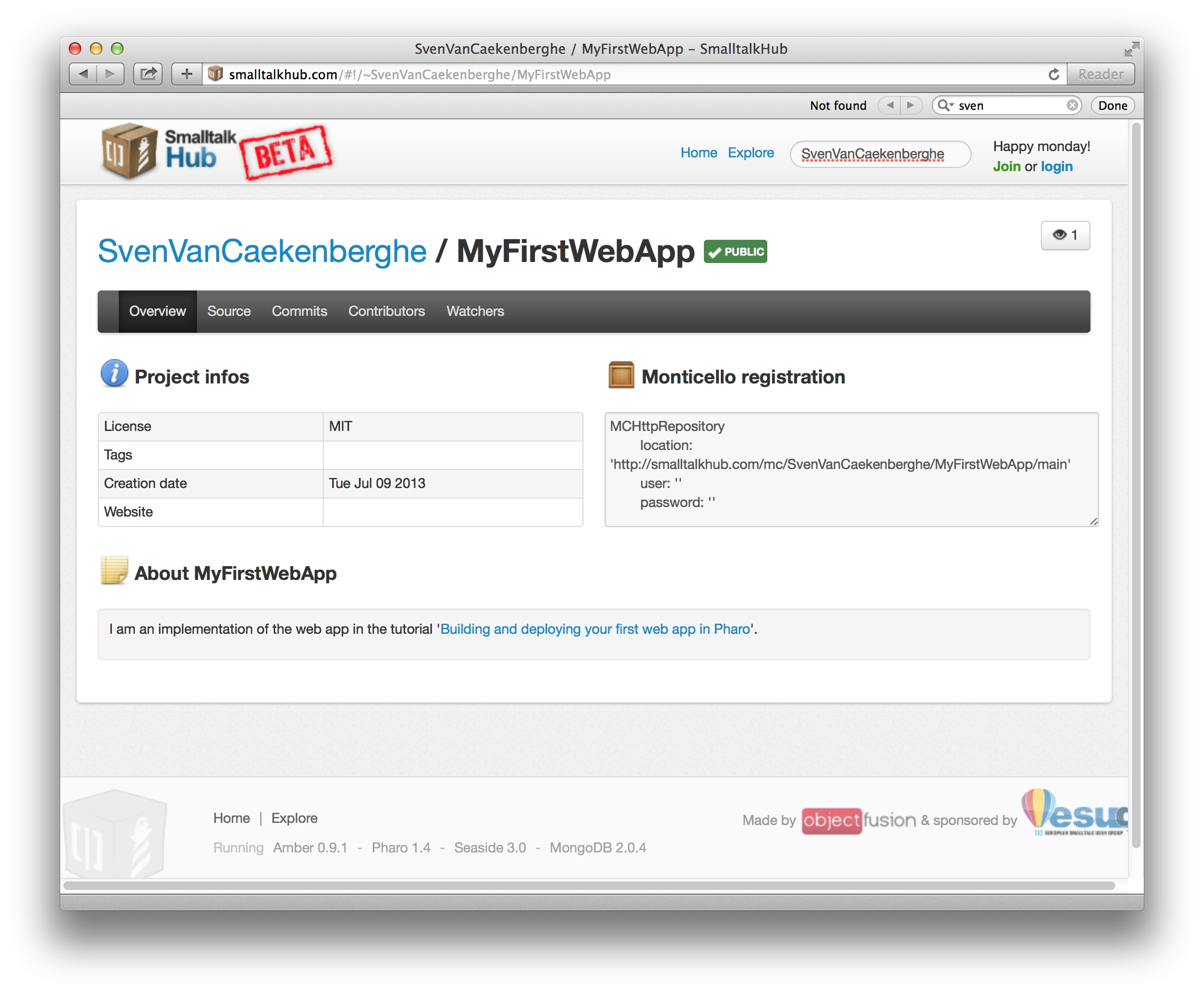

The main place for storing Pharo code is SmalltalkHub http://www.smalltalkhub.com.

Go over there and create yourself a new account.

Once you have an account, create a 'MyFirstWebApp' project.

You can leave the public option checked, it means that you and others

can download the code without having to enter any credentials.

Your project's page should look like the one on Figure 0.14.

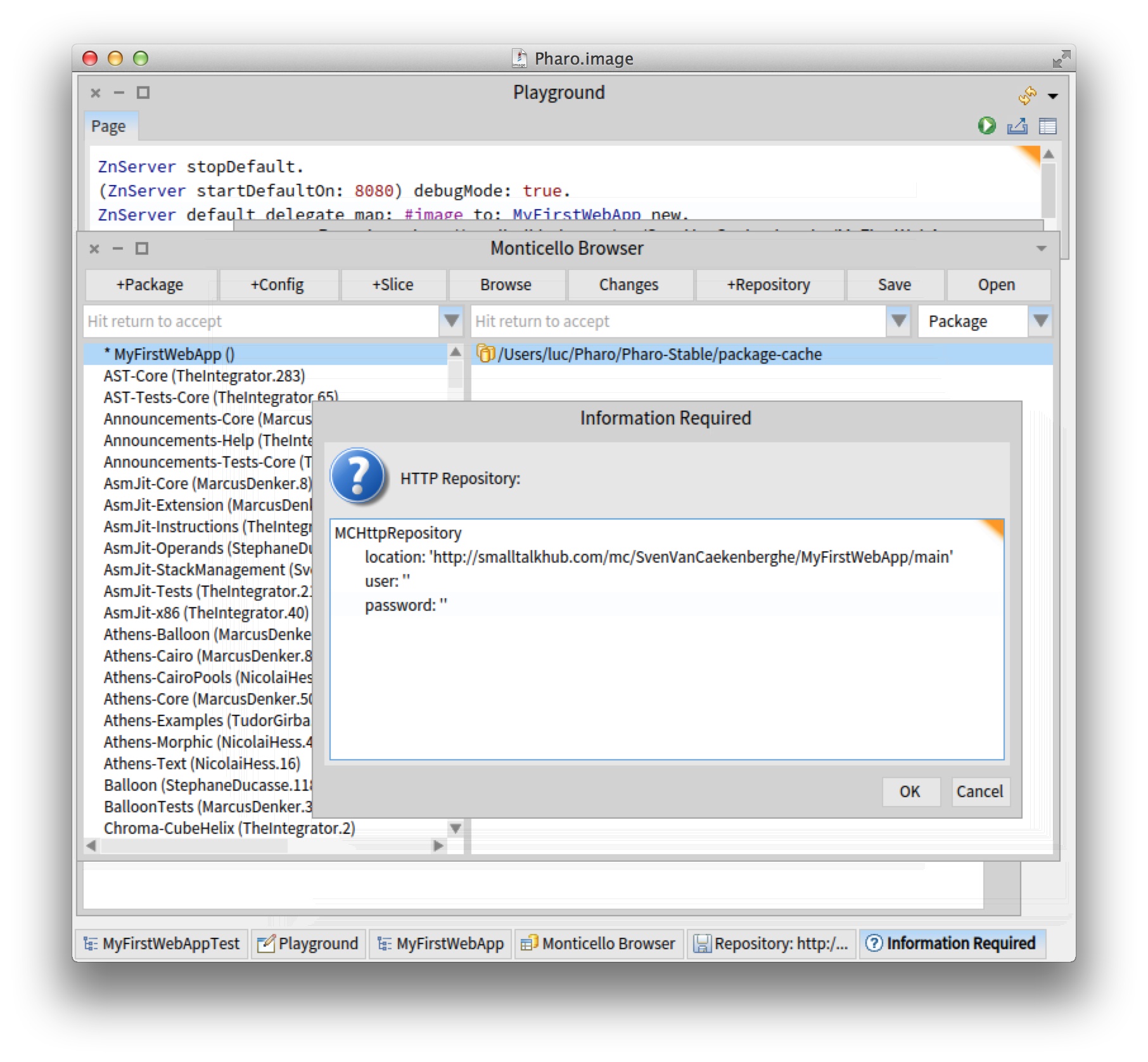

On this page, select and copy the Monticello registration template (make sure to copy the whole contents, including the username and password parts). Now, go back to Pharo and in Monticello, click on the +Repository button (be sure that your package is selected in the left pane).

Select Smalltalkhub.com as repository type and overwrite the presented template with the one you just copied. It should look similar to Figure 0.15. Before accepting, fill in your user(name) and password (between the single quotes), the ones you gave during registration on SmalltalkHub.

Now, Monticello Browser shows you to select repositories to save your package as shown in Figure 0.16.

You may have noticed that there is an asterisk (*) in front of your package name,

indicating the package is dirty: i.e., it has uncommitted changes.

By clicking on the 'Changes' button, Monticello will list everything that has changed or will tell you nothing has changed (this happens sometimes when Monticello gets out of sync). If Monticello finds actual changes, you will get a browser showing all the changes you made.

Since this is the first version, all your changes are additions.

7.2. Committing to SmalltalkHub

Go back to the Monticello Browser and click the 'Save' button (with your package and repository selected). Leave the version name, something like MyFirstWebApp-SvenVanCaekenberghe.1 alone, write a nice commit message in the second pane and press Accept to save your code to SmalltalkHub. When all goes well, you will see an upload progress bar and finally a version window that confirms the commit. You can close it later on.

If something goes wrong, you probably made a typo in your repository specification. You can edit it by right-clicking on it in the Monticello Browser and selecting ‘Edit repository info’. If a save fails, you will get a Version Window after some error message. Don’t close the Version Window. Your code now lives in your local package cache. Click the ‘Copy’ button and select your SmalltalkHub repository to try saving again.

You can now browse back to Smalltalkhub.com to confirm that your code arrived there.

After a successful commit, it is a good idea to save your image. In any case, your package should now no longer be dirty, and there should be no more differences between the local version and the one on SmalltalkHub.

7.3. Defining a Project Configuration

Real software consists of several packages and will depend on extra external libraries and frameworks. In practice, software configuration management, including the management of dependencies and versions, is thus a necessity. To solve this problem, Pharo is using Metacello (the book Deep into Pharo http://deepintopharo.com contains a full chapter on it). And although we don’t really need it for our small example, we are going to use it anyway. Of course, we will not go into details as this is a complex subject.

To create a Metacello configuration, you define an object, what else did you expect?

But we must respect some name conventions so Monticello can help us to generate part of this Metacello configuration.

Open Monticello and click on the +Config button to add the

ConfigurationOfMyFirstWebApp configuration.

With a right click on it, you can "Browse configuration" which open a Nautilus browser on this newly created class.

We are now going to define three methods: one defining a baseline for

our configuration, one defining concrete package versions for that

baseline, and one declaring that version as the stable released

version. Here is the code:

ConfigurationOfMyFirstWebApp>>baseline1: spec

<version: '1-baseline'>

spec for: #common do:[

spec

blessing: #baseline;

repository:

'http://smalltalkhub.com/mc/SvenVanCaekenberghe/MyFirstWebApp/main';

package: 'MyFirstWebApp' ]

ConfigurationOfMyFirstWebApp>>version1: spec

<version: '1' imports: #('1-baseline')>

spec for: #common do: [

spec

blessing: #release;

package: 'MyFirstWebApp'

with: 'MyFirstWebApp-SvenVanCaekenberghe.1' ]

ConfigurationOfMyFirstWebApp>>stable: spec

<symbolicVersion: #'stable'>

spec for: #common version: '1'

Once you committed the project (that consists in both the Metacello configuration and the Monticello package 'MyFirstWebApp'), you can test your configuration by trying to load it.

ConfigurationOfMyFirstWebApp load.Of course, not much will happen since you already have the specified version loaded. For some feedback, make sure the Transcript is open and inspect the above expression.

Now add your SmalltalkHub repository to the ConfigurationOfMyFirstWebApp Monticello package. Double-check the changes in the Monticello Browser, remember we copied a whole class. Now commit by saving to your SmalltalkHub repository. Use the Web interface to verify that all went well.

8. Running a Real Cloud Server

So we created our first Web app and tested it locally. We stored our source code in the SmalltalkHub repository and created a Metacello configuration for it. Now we need a real cloud server to run our Web app.

It used to be hard and expensive to get access to a real server permanently connected to the internet. Not anymore: prices have comes down and operating cloud servers has become a much easier to use service. If you just want to test the deployment of this Pharo Web app, you can use cloud9 (http://c9.io). It freely provides some testing environments after creating an account. Note that cloud9 is for testing purpose only and that a real hosting solution such as Digital Ocean (http://www.digitalocean.com) is better.

For this guide, we will be using Digital Ocean. The entry level server there, which is more than powerful enough for our experiment, costs just $5 a month. If you stop and remove the server after a couple of days, you will only pay cents. Go ahead and make yourself an account and register a credit card.

8.1. Create a Droplet

A server instance is called a Droplet. Click the ‘Create Droplet’ button and fill in the form. Pick a hostname, select the smallest size, pick a region close to you. As operating system image, we’ll be using a 32-bit Ubuntu Linux, version 13.04 x32. You can optionally use an SSH key pair to log in - it is a good idea, see How to Use SSH Keys with DigitalOcean Droplets - just skip this option for now if you are uncomfortable with it, it is not necessary for this tutorial. Finally click the ‘Create Droplet’ button.

In less than a minute, your new server instance will be ready. Your root password will be emailed to you. If you look at your droplets, you should see your new server in the list. Click on it to see its details.

The important step now is to get SSH access to your new server, preferably through a terminal. With the IP address from the control panel and the root password emailed to you, try to log in.

$ ssh [email protected]Your server is freshly installed and includes only the most essential core packages. Now we have to install Pharo on it. One easy way to do this is using the functionality offered by http://get.pharo.org. The following command will install a fresh Pharo 2.0 image together with all other files needed.

# curl get.pharo.org/40+vm | bashMake sure the VM+image combination works by asking for the image version.

# ./pharo Pharo.image printVersion

[version] 4.0 #40614Let's quickly test the stock HTTP server that comes with Pharo, like we did in the third section of this guide.

# ./pharo Pharo.image eval --no-quit 'ZnServer startDefaultOn: 8080'This command will block. Now access your new HTTP server. You should see the Zinc HTTP Components welcome page. If this works, you can press ctrl-C in the terminal to end our test.

8.2. Deploy for Production

We now have a running server. It can run Pharo too, but it is currently using a generic image. How do we get our code deployed? To do this we use the Metacello

configuration. But first, we are going to make a copy of the stock Pharo.image that we downloaded. We want to keep the original clean while we make changes to the copy.

# ./pharo Pharo.image save myfirstwebapp

We now have a new image (and changes) file called myfirstwebapp.image (and myfirstwebapp.changes). Through the config command line option we can load our

Metacello configuration. Before actually loading anything, we will ask for all available versions to verify that we can access the repository.

# ./pharo myfirstwebapp.image config \

http://smalltalkhub.com/mc/SvenVanCaekenberghe/MyFirstWebApp/main \

ConfigurationOfMyFirstWebApp

'Available versions for ConfigurationOfMyFirstWebApp'

1

1-baseline

bleedingEdge

last

stableYou should have only one version, all the above are equivalent references to the same version. Now we will load and install the stable version.

# ./pharo myfirstwebapp.image config \

http://smalltalkhub.com/mc/SvenVanCaekenberghe/MyFirstWebApp/main \

ConfigurationOfMyFirstWebApp --install=stable

'Installing ConfigurationOfMyFirstWebApp stable'

Loading 1 of ConfigurationOfMyFirstWebApp...

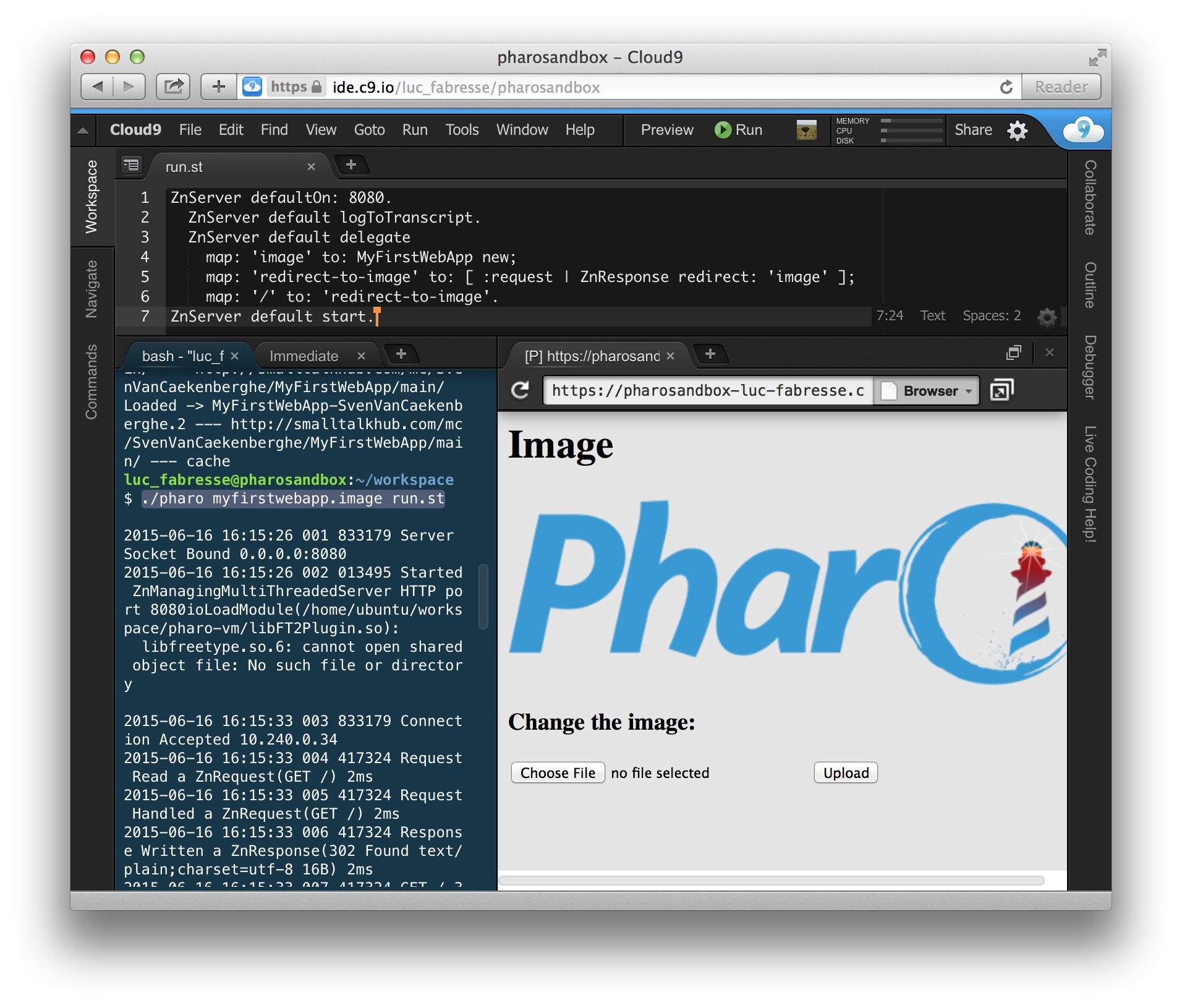

...After loading all necessary code, the config option will also save our image so that it now permanently includes our code. Although we could try to write a (long) one line expression to start our Web app in a server and pass it to the eval option, it is better to write a small script. Create a file called ‘run.st’ with the following contents:

ZnServer defaultOn: 8080.

ZnServer default logToTranscript.

ZnServer default delegate

map: 'image' to: MyFirstWebApp new;

map: 'redirect-to-image' to: [ :request | ZnResponse redirect: 'image' ];

map: '/' to: 'redirect-to-image'.

ZnServer default start.

We added a little twist here: we changed the default root (/) handler to redirect to our new /image Web app. Test the startup script like this:

# ./pharo myfirstwebapp.image run.st

2015-06-15 15:59:56 001 778091 Server Socket Bound 0.0.0.0:8080

2015-06-15 15:59:56 002 013495 Started ZnManagingMultiThreadedServer HTTP port 8080

...

You can surf to the correct IP address and port to test you application. Note that /welcome, /help and /image are still available too. Type ctrl-c to kill the server again. You can then put the server in background, running for real.

# nohup ./pharo myfirstwebapp.image run.st &

Figure 0.17 shows how the deployment looks like on cloud9.

9. Have Fun Extending this Web App

Did you like the example so far? Would you like to take one more step? Here is a little extension left as an exercise. Add an extra section at the bottom of the main page that shows a miniature version of the previous image. Initially, you can show an empty image. Here are a couple of hints. Read only as far as you need, try to figure it out by yourself.

9.1. Hint 1

You can scale a form object into another one using just one message taking a single argument. You can use the same classes that we used for parsing as a tool to generate PNG, JPEG or GIF images given a form.

When you are done, save your code as a new version. Then update your configuration with a new, stable version. Finally, go to the server, update your image based on the configuration and restart the running vm+image.

9.2. Hint 2

Change the html method referring to a new variant, /image?previous=true, for the second image. Adjust handleGetRequest: to look for that attribute.

Add a helper method pngImageEntityForForm: and a previousImage accessor.

It is easy to create an empty, blank form as default.

Call a updatePreviousImage at the right spot in handlePostRequest: and implement the necessary functionality there.

9.3. Hint 3

If you found it difficult to find the right methods, have a look at the following ones:

Form>>scaledIntoFormOfSize:Form class>>extent:depth:PNGReadWriter>>nextPutImage:ByteArray class>>streamContents:ZnByteArrayEntity class>>with:type:

9.4. Solution, Part 1, New Methods

Here are 3 new methods that are part of the solution.

pngImageEntityForForm: form

^ ZnByteArrayEntity

with: (ByteArray streamContents: [ :out |

(PNGReadWriter on: out) nextPutImage: form ])

type: ZnMimeType imagePng

previousImage

^ previousImage ifNil: [

| emptyForm |

emptyForm:= Form extent: 128 @ 128 depth: 8.

previousImage := self pngImageEntityForForm: emptyForm ]

updatePreviousImage

| form scaled |

form := self form.

scaled := form scaledIntoFormOfSize: 128.

previousImage := self pngImageEntityForForm: scaled9.5. Solution, Part 2, Changed Methods

Here are the changes to 3 existing methods for the complete solution.

html

^ '<html><head><title>Image</title>

<body>

<h1>Image</h1>

<img src="image?raw=true"/>

<br/>

<form enctype="multipart/form-data" action="image" method="POST">

<h3>Change the image:</h3>

<input type="file" name="file"/>

<input type="submit" value= "Upload"/>

</form>

<h3>Previous Image</h3>

<img src="image?previous=true"/>

</body></html>'

handleGetRequest: request

(request uri queryAt: #raw ifAbsent: [ nil ])

ifNotNil: [ ^ ZnResponse ok: self image ].

(request uri queryAt: #previous ifAbsent: [ nil ])

ifNotNil: [ ^ ZnResponse ok: self previousImage ].

^ ZnResponse ok: (ZnEntity html: self html)

handlePostRequest: request

| part newImage badRequest |

badRequest := [ ^ ZnResponse badRequest: request ].

(request hasEntity

and: [ request contentType matches: ZnMimeType multiPartFormData ])

ifFalse: badRequest.

part := request entity

partNamed: #file

ifNone: badRequest.

newImage := part entity.

(newImage notNil

and: [ newImage contentType matches: 'image/*' asZnMimeType ])

ifFalse: badRequest.

[ self formForImageEntity: newImage ]

on: Error

do: badRequest.

self updatePreviousImage.

image := newImage.

^ ZnResponse redirect: #image9.6. Solution, Part 3, Updated Configuration

To update our configuration, add 1 method and change 1 method.

version2: spec

<version: '2' imports: #('1-baseline')>

spec for: #common do: [

spec

blessing: #release;

package: 'MyFirstWebApp' with: 'MyFirstWebApp-SvenVanCaekenberghe.2' ]

stable: spec

<symbolicVersion: #'stable'>

spec for: #common version: '2'Of course, you will have to substitute your name for the concrete version.

10. Conclusion

Congratulations: you have now built and deployed your first Web app with Pharo. Hopefully you are interested in learning more. From the Pharo website you should be able to find all the information you need. Don’t forget about the Pharo by Example book and the mailing lists. This guide was an introduction to writing Web applications using Pharo, touching on the fundamentals of HTTP. Like we mentioned in the introduction, there are a couple of high level frameworks that offer more extensive support for writing Web applications. The three most important ones are Seaside, AIDAweb and Iliad.

The code of the Web app, including tests and the Metacello

configuration, is on SmalltalkHub.

A similar example is also included in the Zinc HTTP Components project itself, under the name ZnImageExampleDelegate[Tests].