Zinc HTTP: The Client Side

HTTP is arguably the most important application level network protocol for what we consider to be the Internet. It is the protocol that allows web browsers and web servers to communicate. It is also becoming the most popular protocol for implementing web services.

With Zinc, Pharo has out of the box support for HTTP. Zinc is a robust, fast and elegant HTTP client and server library written and maintained by Sven van Caekenberghe.

1. HTTP and Zinc

HTTP, short for Hypertext Transfer Protocol, functions as a request-response protocol in the client-server computing model. As an application level protocol it is layered on top of a reliable transport such as a TCP socket stream. The most important standard specification document describing HTTP version 1.1 is RFC 2616. As usual, a good starting point for learning about HTTP is its Wikipedia article.

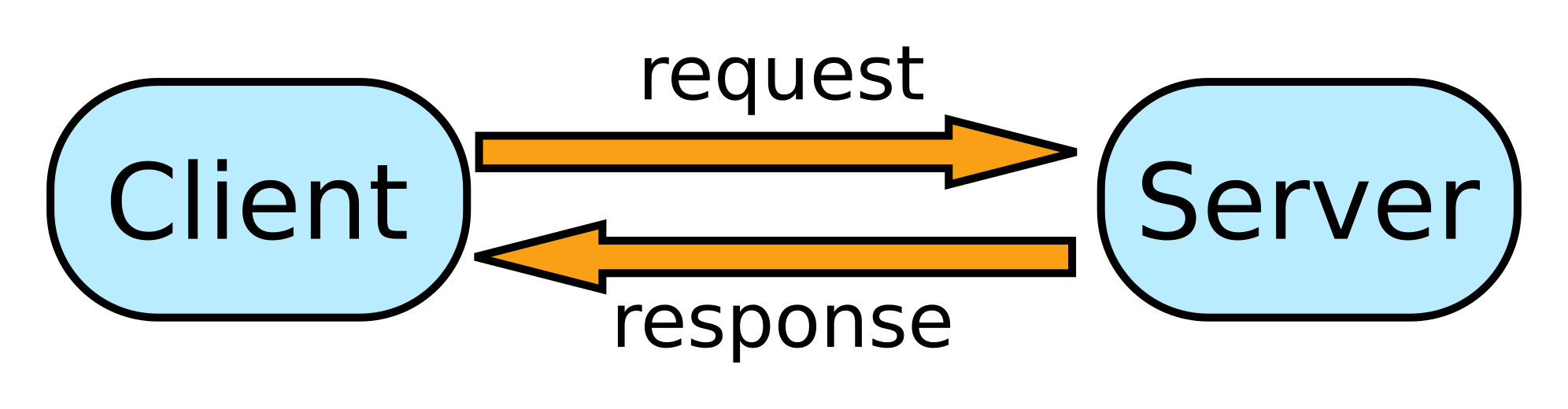

A client, often called user-agent, submits an HTTP request to a server which will respond with an HTTP response (see Fig. 0.1). The initiative of

the communication lies with the client. In HTTP parlance, the client requests a resource. A resource, sometimes also called an entity, is the combination of a

collection of bytes and a mime-type. A simple text resource will consist of bytes encoding the string in some encoding, for example UTF-8, and the mime-type

text/plain;charset=utf-8, in contrast, an HTML resource will have a mime-type like text/html;charset=utf-8.

To specify which resource you want, a URL (Uniform Resource Locator) is used. Web addresses are the most common form of URL. Consider for example http://pharo.org/files/pharo-logo-small.png : it is a URL that refers to a PNG image resource on a specific server.

The reliable transport connection between an HTTP client and server is used bidirectionally: both to send the request as well as to receive the response. It can be used for just one request/response cycle, as was the case for HTTP version 1.0, or it can be reused for multiple request/response cycles, as is the default for HTTP version 1.1.

Zinc, the short form for Zinc HTTP Components, is an open-source Smalltalk framework to deal with HTTP. It models most concepts of HTTP and its related standards and offers both client and server functionality. One of its key goals is to offer understandability (Smalltalk's design principle number one). Anyone with a basic understanding of Smalltalk and the HTTP principles should be able to understand what is going on and learn, by looking at the implementation. Zinc, or Zn, after its namespace prefix, is an integral part of Pharo Smalltalk since version 1.3. It has been ported to other Smalltalk implementations such as Gemstone.

The reference Zn implementation lives in several places:

- http://www.squeaksource.com/ZincHTTPComponents

- http://mc.stfx.eu/ZincHTTPComponents

- https://www.github.com/svenvc/zinc

Installation or updating instructions can be found on its web site.

2. Doing a Simple Request

The key object to programmatically execute HTTP requests is called ZnClient. You instantiate it, use its rich API to configure and execute an HTTP request

and access the response. ZnClient is a stateful object that acts as a builder.

2.1. Basic Usage

Let's get started with the simplest possible usage.

ZnClient new get: 'http://zn.stfx.eu/zn/small.html'.

Select the expression and print its result. You should get a String back containing a very small HTML document. The get: method

belongs to the convenience API. Let's use a more general API to be a bit more explicit about what happened.

ZnClient new

url: 'http://zn.stfx.eu/zn/small.html';

get;

response.

Here we explicitly set the url of the resource to access using url:, then we execute an HTTP GET using get and we finally ask for the response object

using response. The above returns a ZnResponse object. Of course you can inspect it. It consists of 3 elements:

- a

ZnStatusLineobject, - a

ZnHeadersobject and - an optional

ZnEntityobject.

The status line says HTTP/1.1 200 OK, which means the request was successful. This can be tested by sending isSuccess to either the response object or the

client itself. The headers contain meta data related to the response, including:

- the content-type (a mime-type), accessible with the

contentTypemessage - the content-length (a byte count), accessible with the

contentLengthmessage - the date the response was generated

- the server that generated the response

The entity is the actual resource: the bytes that should be interpreted in the context of the content-type mime-type. Zn automatically converts non-binary

mime-types into Strings using the correct encoding. In our example, the entity is an instance of ZnStringEntity, a concrete subclass of ZnEntity.

Like any Smalltalk object, you can inspect or explore the ZnResponse object. You might be wondering how this response was actually transferred over the

network. That is easy with Zinc, as the key HTTP objects all implement writeOn: that displays the raw format of the response i.e. what has been transmitted

through the network.

| response |

response := (ZnClient new)

url: 'http://zn.stfx.eu/zn/small.html';

get;

response.

response writeOn: Transcript.

Transcript flush.If you have the Transcript open, you should see something like the following:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Thu, 26 Mar 2015 23:26:49 GMT

Modification-Date: Thu, 10 Feb 2011 08:32:30 GMT

Content-Length: 113

Server: Zinc HTTP Components 1.0

Vary: Accept-Encoding

Content-Type: text/html;charset=utf-8

<html>

<head><title>Small</title></head>

<body><h1>Small</h1><p>This is a small HTML document</p></body>

</html>The first CRLF terminated line is the status line. Next are the headers, each on a line with a key and a value. An empty line ends the headers. Finally, the entity bytes follows, either up to the content length or up to the end of the stream.

You might wonder what the request looked like when it went over the network? You can find it out using the same technique.

| request |

request := (ZnClient new)

url: 'http://zn.stfx.eu/zn/small.html';

get;

request.

request writeOn: Transcript.

Transcript flush.In an opened Transcript you will now see:

GET /zn/small.html HTTP/1.1

Accept: */*

User-Agent: Zinc HTTP Components 1.0

Host: zn.stfx.eu

A ZnRequest object consists of 3 elements:

- a

ZnRequestLineobject, - a

ZnHeadersobject and - an optional

ZnEntityobject.

The request line contains the HTTP method (sometimes called verb), URL and the HTTP protocol version. Next come the request headers, similar to the response headers, meta data including:

- the host we want to talk to,

- the kind of mime-types that we accept or prefer, and

- the user-agent that we are.

If you look carefully at the Transcript you will see the empty line terminating the headers. For most kinds of requests, like for a GET, there is no entity.

For debugging and for learning, it can be helpful to enable logging on the client. Try the following.

ZnClient new

logToTranscript;

get: 'http://zn.stfx.eu/zn/small.html'.This will print out some information on the Transcript, as shown below.

2015-03-26 20:32:30 001 Connection Established zn.stfx.eu:80 46.137.113.215 223ms

2015-03-26 20:32:30 002 Request Written a ZnRequest(GET /zn/small.html) 0ms

2015-03-26 20:32:30 003 Response Read a ZnResponse(200 OK text/html;charset=utf-8 113B) 223ms

2015-03-26 20:32:30 004 GET /zn/small.html 200 113B 223msIn a later subsection about server logging, which uses the same mechanism, you will learn how to interpret and customize logging.

2.2. Simplified HTTP Requests

Although ZnClient is absolutely the preferred object to deal with all the intricacies of HTTP, you sometimes wish you could to a quick HTTP request with an

absolute minimum amount of typing, especially during debugging. For these occasions there is ZnEasy, a class side only API for quick HTTP requests.

ZnEasy get: 'http://zn.stfx.eu/zn/numbers.txt'.

The result is always a ZnResponse object. Apart from basic authentication, there are no other options. A nice feature here, more as an example, is some

direct ways to ask for image resources as ready to use Forms.

ZnEasy getGif:

'http://esug.org/data/Logos+Graphics/ESUG-Logo/2006/gif/',

'esug-Logo-Version3.3.-13092006.gif'.

ZnEasy getJpeg: 'http://caretaker.wolf359.be/sun-fire-x2100.jpg'.

ZnEasy getPng: 'http://pharo.org/files/pharo.png'.

(ZnEasy getPng: 'http://chart.googleapis.com/chart?cht=tx&chl=',

'a^2+b^2=c^2') asMorph openInHand.

When you explore the implementation, you will notice that ZnEasy uses a ZnClient object internally.

3. HTTP Success ?

A simple view of HTTP is: you request a resource and get a response back containing the resource. But even if the mechanics of HTTP did work, and even that is not guaranteed (see the next section), the response could not be what you expected.

HTTP defines a whole set of so called status codes to define various situations. These codes turn up as part of the status line of a response. The dictionary mapping numeric codes to their textual reason string is predefined.

ZnConstants httpStatusCodes.

A good overview can be found in the Wikipedia article List of HTTP status codes. The most common code,

the one that indicates success is numeric code 200 with reason 'OK'. Have a look at the testing protocol of ZnResponse for how to interpret some of them.

So if you do an HTTP request and get something back, you cannot just assume that all is well. You first have to make sure that the call itself (more

specifically the response) was successful. As mentioned before, this is done by sending isSuccess to the response or the client.

| client |

client := ZnClient new.

client get: 'http://zn.stfx.eu/zn/numbers.txt'.

client isSuccess

ifTrue: [ client contents lines collect: [ :each | each asNumber ] ]

ifFalse: [ self inform: 'Something went wrong' ]

To make it easier to write better HTTP client code, ZnClient offers some useful status handling methods in its API. You can ask the client to consider

non-successful HTTP responses as errors with the enforceHTTPSuccess option. The client will then automatically throw a ZnHTTPUnsuccesful exception. This

is generally useful when the application code that uses Zinc handles errors.

Additionally, to install a local failure handler, there is the ifFail: option. This will invoke a block, optionally passing an exception, whenever something

goes wrong. Together, this allows the above code to be rewritten as follows.

ZnClient new

enforceHttpSuccess: true;

ifFail: [ :ex | self inform: 'Cannot get numbers: ', ex printString ];

get: 'http://zn.stfx.eu/zn/numbers.txt'.

Maybe it doesn't look like a big difference, but combined with some other options and features of ZnClient that we'll see later on, the code does become more

elegant and more reliable at the same time.

4. Dealing with Networking Reality

As a network protocol, HTTP is much more complicated than an ordinary message send. The famous Fallacies of Distributed Computing paper by Deutsch et. al. eloquently lists the issues involved:

- The network is reliable.

- Latency is zero.

- Bandwidth is infinite.

- The network is secure.

- Topology doesn't change.

- There is one administrator.

- Transport cost is zero.

- The network is homogeneous.

Zn will signal various exceptions when things go wrong, at different levels. ZnClient and the underlying framework have constants, settings and options to

deal with various aspects related to these issues.

Doing an HTTP request-response cycle can take an unpredictable amount of time. Client code has to specify a timeout: the maximum amount of time to wait for a response, and be prepared for when that timeout is exceeded. When there is no answer within a specified timeout can mean that some networking component is extremely slow, but it could also mean that the server simply refuses to answer.

Setting the timeout directly on a ZnClient is the easiest.

ZnClient new

timeout: 1;

get: 'http://zn.stfx.eu/zn/small.html'.

The timeout counts for each socket level connect, read and write operation, separately. You can dynamically redefine the timeout using the ZnConnectionTimeout

class, which is a DynamicVariable subclass.

ZnConnectionTimeout

value: 5

during: [ ^ ZnClient new get: 'http://zn.stfx.eu/zn/small.html' ].Zn defines its global default timeout in seconds as a setting.

ZnNetworkingUtils defaultSocketStreamTimeout.

ZnNetworkingUtils defaultSocketStreamTimeout: 60.This setting affects most framework level operations, if nothing else is specified.

During the execution of HTTP, various network exceptions, as subclasses of NetworkError, might be thrown. These will all be caught by the ifFail: block when installed.

To deal with temporary or intermittent network or server problems, ZnClient offers a retry protocol. You can set how many times a request should be retried

and how many seconds to wait between retries.

ZnClient new

numberOfRetries: 3;

retryDelay: 2;

get: 'http://zn.stfx.eu/zn/small.html'.In the above example, the request will be tried up to 3 times, with a 2 second delay between attempts. Note that the definition of failure/success is broad: it includes for example the option to enforce HTTP success.

5. Building URL's

Zn uses ZnUrl objects to deal with URLs. ZnClient also contains an API to build URLs. Let us revisit our initial example, using explicit URL construction with the ZnClient API.

ZnClient new

http;

host: 'zn.stfx.eu';

addPath: 'zn';

addPath: 'small.html';

get.

Instead of giving a string argument to be parsed into a ZnUrl, we now provide the necessary elements to construct the URL manually, by sending messages to

our ZnClient object. With http we set what is called the scheme. Then we set the hostname. Since we don't specify a port, the default port for HTTP will

be used, port 80. Next we add path elements, extending the path one by one.

A URL can also contain query parameters. Let's do a Google search as an example:

ZnClient new

http;

host: 'www.google.com';

addPath: 'search';

queryAt: 'q' put: 'Pharo Smalltalk';

get.

Query parameters have a name and a value. Certain special characters have to be encoded. You can build the same URL with the ZnUrl object, in several ways.

ZnUrl new

scheme: #http;

host: 'www.google.com';

port: 80;

addPathSegment: 'search';

queryAt: 'q' put: 'Pharo Smalltalk';

yourself.If you print the above expression, it gives you the printable representation of the URL.

http://www.google.com/search?q=Pharo%20Smalltalk

This string version can easily be parsed again into a ZnUrl object

'http://www.google.com/search?q=Pharo%20Smalltalk' asZnUrl. 'http://www.google.com:80/search?q=Pharo Smalltalk' asZnUrl.

Note how the ZnUrl parser is forgiving with respect to the space, like most browsers would do. When producing an external representation, proper encoding

will take place. Please consult the class comment of ZnUrl for a more detailed look at the capabilities of ZnUrl as a standalone object.

6. Submitting HTML Forms

In many web applications HTML forms are used. Examples are forms to enter a search string, a form with a username and password to log in or complex registration

forms. In the classic and most common way, this is implemented by sending the data entered in the fields of a form to the server when a submit button is clicked.

It is possible to implement the same behavior programmatically using ZnClient.

First you have to find out how the form is implemented by looking at the HTML code. Here is an example.

<form action="search-handler" method="POST" enctype="application/x-www-form-urlencoded">

Search for: <input type="text" name="search-field"/>

<input type="submit" value="Go!"/>

</form>

This form shows one text input field, preceded by a ‘Search for:’ label and followed by a submit button with ‘Go!’ as label. Assuming this appears on a page with

URL http://www.search-engine.com/, we can implement the behavior of the browser when the user clicks the button, submitting or sending the form data to the server.

ZnClient new

url: 'http://www.search-engine.com/search-handler';

formAt: 'search-field' put: 'Pharo Smalltalk';

post.

The URL is composed by combining the URL of the page that contains the form with the action specified. There is no need to set the encoding of the request here

because the form uses the default encoding application/x-www-form-urlencoded. By using the formAt:put: method to set the value of a field, an entity of

type ZnApplicationFormUrlEncodedEntity will be created if needed, and the field name/value association will be stored in it. When finally post is invoked,

the HTTP request sent to the server will include a properly encoded entity. As far as the server is concerned, it will seem as if a real user submitted the form.

Consequently, the response should be the same as when you submit the form manually using a browser. Be careful to include all relevant fields, even the hidden ones.

There is a second type of form encoding called multipart/form-data. Here, instead of adding fields, you add ZnMimePart instances.

<form action="search-handler" method="POST" enctype="multipart/form-data">

Search for: <input type="text" name="search-field"/>

<input type="submit" value="Go!"/>

</form>The code to submit this form would then be as follows.

ZnClient new

url: 'http://www.search-engine.com/search-handler';

addPart: (ZnMimePart

fieldName: 'search-field'

value: 'Pharo Smalltalk');

post.

In this case, an entity of type ZnMultiPartFormDataEntity is created and used. This type is often used in forms that upload files. Here is an example.

<form action="upload-handler" method="POST" enctype="multipart/form-data">

Photo file: <input type="file" name="photo-file"/>

<input type="submit" value="Upload!"/>

</form>This would be the way to do the upload programmatically.

ZnClient new

url: 'http://www.search-engine.com/upload-handler';

addPart: (ZnMimePart

fieldName: 'photo-file'

fileNamed: '/Pictures/cat.jpg');

post.

Sometimes, the form's submit method is GET instead of POST, just send get instead of post to the client. Note that this technique of sending form data to

a server is different than what happens with raw POST or PUT requests using a REST API. In a later subsection we will come back to this.

7. Basic Authentication, Cookies and Sessions

There are various techniques to add authentication, a mechanism to control who accesses which resources, to HTTP. This is orthogonal to HTTP itself. The simplest and most common form of authentication is called 'Basic Authentication'.

ZnClient new

username: '[email protected]' password: 'trustno1';

get: 'http://www.example.com/secret.txt'.

That is all there is to it. If you want to understand how this works, look at how ZnRequest>>#setBasicAuthenticationUsername:password: is implemented.

Basic authentication over plain HTTP is insecure because it transfers the username/password combination obfuscated by encoding it using the trivial Base64 encoding. When used over HTTPS, basic authentication is secure though. Note that when sending multiple requests while reusing the same client, authentication is reset for each request, to prevent the accidental transfer of sensitive data.

Basic authentication is not the same as a web application where you have to log in using a form. In such web applications, e.g an online store that has a login part and a shopping cart per user, state is needed. During the interaction with the web application, the server needs to know that your requests/responses are part of your session: you log in, you add items to your shopping cart and you finally check out and pay. It would be problematic if the server mixed the requests/responses of different users. However, HTTP is by design a stateless protocol: each request/response cycle is independent. This principle is crucial to the scalability of the internet.

The most commonly used technique to overcome this issue, enabling the tracking of state across different request/response cycles is the use of so called cookies. Cookies are basically key/value pairs connected to a specific server domain. Using a special header, the server asks the client to remember or update the value of a cookie for a domain. On subsequent requests to the same domain, the client will use a special header to present the cookie and its value back to the server. Semantically, the server manages a key/value pair on the client.

As we saw before, a ZnClient instance is essentially stateful. It not only tries to reuse a network connection but it also maintains a

ZnUserAgentSession object, which represents the session. One of the main functions of this session object is to manage cookies, just like your browser does. ZnCookie objects are held

in a ZnCookieJar object inside the session object.

Cookie handling will happen automatically. This is a hypothetical example of how this might work, assuming a site where you have to log in before you are able to access a specific file.

ZnClient new

url: 'http://cloud-storage.com/login';

formAt: 'username' put: '[email protected]';

formAt: 'password' put: 'trustno1';

post;

get: 'http://cloud-storage.com/my-file'.

After the post, the server will presumably set a cookie to acknowledge a successful login. When a specific file is next requested from the same domain, the

client presents the cookie to prove the login. The server knows it can send back the file because it recognizes the cookie as valid. By sending session to

the client object, you can access the session object and then the remembered cookies.

8. PUT, POST, DELETE and other HTTP Methods

A regular request for a resource is done using a GET request. A GET request does not send an entity to the server. The only way for a GET request to transfer information to the server is by encoding it in the URL, either in the path or in query variables. (To be 100% correct we should add that data can be sent as custom headers as well.)

8.1. PUT and POST Methods

HTTP provides for two methods (or verbs) to send information to a server. These are called PUT and POST. They both send an entity to the server in order to transfer data.

In the subsection about submitting HTML forms we already saw how POST is used to send either a ZnApplicationFormUrlEncodedEntity or to send a ZnMultiPartFormDataEntity containing structured data to a server.

Apart from that, it is also possible to send a raw entity to a server. Of course, the server needs to be prepared to handle this kind of entity coming in. Here are a couple of examples of doing a raw PUT and POST request.

ZnClient new

put: 'http://zn.stfx.eu/echo' contents:'Hello there!'.

ZnClient new

post: 'http://zn.stfx.eu/echo' contents: #[0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9].

ZnClient new

entity: (ZnEntity

with: '<xml><object><id>42</id></object></xml>'

type: ZnMimeType applicationXml);

post.

In the last example we explicitly set the entity to be XML and do a POST. In the first two examples, the convenience contents system is used to automatically

create a ZnStringEntity of the type ZnMimeType textPlain, respectively a ZnByteArrayEntity of the type ZnMimeType applicationOctectStream.

The difference between PUT and POST is semantic. POST is generally used to create a new resource inside an existing collection or container, or to initiate some

action or process. For this reason, the normal response to a POST request is to return the URL (or URI) of the newly created resource. Conventionally, the reponse

contains this URL both in the Location header accessible via the message location and in the entity part.

When a POST successfully created the resource, its HTTP response will be 201 Created. PUT is generally used to update an existing resource of which you know the exact URL (or URI). When a PUT is successful, its HTTP response will be just 200 OK and nothing else will be returned. When we will discuss REST Web Service APIs, we will come back to this.

8.2. DELETE and other Methods

The fourth member of the common set of HTTP methods is DELETE. It is very similar to both GET and PUT: you just specify an URL of the resource that you want to delete or remove. When successful, the server will just reply with a 200 OK. That is all there is to it.

Certain HTTP based protocols, like WebDAV, use even more HTTP methods. These can be queried explicitly using the method: setter and the execute operation.

ZnClient new

url: 'http://www.apache.org';

method: #OPTIONS;

execute;

response.

An OPTIONS request does not return an entity, but only meta data that are included in the header of the response. In this example, the response header contains

an extra meta data named Allow which specifies the list of HTTP methods that may be used on the resource.

9. Reusing Network Connections, Redirect Following and Checking for Newer Data

9.1. ZnClient Lifecycle

HTTP 1.1 defaults to keeping the client connection to a server open, and the server will do the same. This is useful and faster if you need to issue more than

one request. ZnClient implements this behavior by default.

Array streamContents: [ :stream | | client |

client := ZnClient new url: 'http://zn.stfx.eu'.

(1 to: 10) collect: [ :each | | url |

url := '/random/', each asString.

stream nextPut: (client path: url; get) ].

client close ].The above example sets up a client to connect to a specific host. Then it collects the results of 10 different requests, asking for random strings of a specific size. All requests will go over the same network connection.

Neither party is required to keep the connection open for a long time, as this consumes resources. Both parties should be prepared to deal with connections

closing, this is not an error. ZnClient will try to reuse an existing connection and reconnect once if this reuse fails. The option connectionReuseTimeout

limits the maximum age for a connection to be reused.

Note how we also close the client using the message close. A network connection is an external resource, like a file, that should be properly closed after use.

If you don't do that, they will get cleaned up eventually by the system, but it is more efficient to do it yourself.

In many situations, you only want to do one single request. HTTP 1.1 has provisions for this situation. The beOneShot option of ZnClient will do just that.

ZnClient new

beOneShot;

get: 'http://zn.stfx.eu/numbers.txt'.

With the beOneShot option, the client notifies the server that it will do just one request and both parties will consequently close the connection after use,

automatically. In this case, an explicit close of the ZnClient object is no longer needed.

9.2. Redirects

Sometimes when requesting a URL, an HTTP server will not answer immediately but redirect you to another location. For example, Seaside actually does this on each

request. This is done with a 301 or 302 response code. You can ask a ZnResponse whether it's a redirect with isRedirect. In case of a redirect response,

the Location header will contain the location the server redirects you to. You can access that URL using location.

By default, ZnClient will follow redirects automatically for up to 3 redirects. You won't even notice unless you activate logging. If for some reason you

want to disable this feature, send a followRedirects: false to your client. To modify the maximum number of redirects that could be followed, use maxNumberOfRedirects:.

Following redirects can be tricky when PUT or POST are involved. Zn implements the common behavior of changing a redirected PUT or POST into a GET while dropping the body entity. Cookies will be resubmitted. Zn also handles relative redirect URLs, although these are not strictly part of the standard.

9.3. If-Modified-Since

A client that already requested a resource in the past can also ask a server if that resource has been modified, i.e. is newer, since he last requested it. If so,

the server will give a quick 304 Not Modified response without sending the resource over again. This is done by setting the If-Modified-Since header using ifModifiedSince:.

This works both for regular requests as well as for downloads.

ZnClient new

url: 'http://zn.stfx.eu/zn/numbers.txt';

setIfModifiedSince: (Date year: 2011 month: 1 day: 1);

downloadTo: FileLocator imageDirectory.

ZnClient new

url: 'http://zn.stfx.eu/zn/numbers.txt';

setIfModifiedSince: (Date year: 2012 month: 1 day: 1);

get;

response.For this to work, the server has to honor this particular protocol interaction, of course.

10. Content-Types, Mime-Types and the Accept Header

Asking for a resource with a certain mime-type does not mean that the server will return something of this type. The extension at the end of a URL has no real

significance, and the server might have been reconfigured since last you asked for this resource. For example, asking for http://example.com/foo,

http://example.com/foo.txt or http://example.com/foo.text could all be the same or all be different, and this may change over time. This is why HTTP resources

(entities) are accompanied by a content-type: a mime-type that is an official, cross-platform definition of a file or document type or format. Again, see the

Wikipedia article Internet media type for more details.

Zn models mime-types using its ZnMimeType object which has 3 components:

- a main type, for example text or image,

- a sub type, for example plain or html, or jpeg, png or gif, and

- a number of attributes, for example

charset=utf-8.

The class side of ZnMimeType has some convenience methods for accessing well known mime-types, for example:

ZnMimeType textHtml.

Note that for textual (non-binary) types, the encoding defaults to UTF-8, the prevalent internet standard. Creating a ZnMimeType object is also as easy as

sending asZnMimeType to a String.

'text/html;charset=utf-8' asZnMimeType.

The subtype can be a wildcard, indicated by a *. This allows for matching.

ZnMimeType textHtml matches: ZnMimeType text.

With ZnClient you can set the accept request header to indicate what you as a client expect, and optionally enforce that the server returns the type you asked for.

ZnClient new

enforceAcceptContentType: true;

accept: ZnMimeType textPlain;

get: 'http://zn.stfx.eu/zn/numbers.txt'.

The above code indicates to the server that we want a text/plain type resource by means of the Accept header. When the response comes back and it is not

of that type, the client will raise a ZnUnexpectedContentType exception. Again, this will be handled by the ifFail: block, when specified.

11. Headers

HTTP meta data, both for requests and for responses, is specified using headers. These are key/value pairs, both strings. A large number of predefined headers

exists, see this List of HTTP header fields. The exact semantics of each header, especially their value, can be very

complicated. Also, although headers are key/value pairs, they are more than a regular dictionary. There can be more values for the same key and keys are often

written using a canonical capitalization, like Content-Type.

HTTP provides for a way to do a request, just like a regular GET but with a response that contains only the meta data, the status line and headers, but not the actual resource or entity. This is called a HEAD request.

ZnClient new

head: 'http://zn.stfx.eu/zn/small.html';

response.

Since there is no content, we have to look at the headers of the response object. Note that the content-type and content-length headers will be set, as if

there was an entity, although none is transferred.

ZnClient allows you to easily specify custom headers for which there is not yet a predefined accessor, which is most of them. At the framework level,

ZnResponse and ZnRequest offer some more predefined accessors, as well as a way to set and query any custom header by accessing their headers sub object.

The following are all equivalent:

ZnClient new accept: 'text/*'.

ZnClient new request setAccept: 'text/*'.

ZnClient new request headers at: 'Accept' put: 'text/*'.

ZnClient new request headers at: 'ACCEPT' put: 'text/*'.

ZnClient new request headers at: 'accept' put: 'text/*'.Once a request is executed, you can query the response headers like this:

client response isConnectionClose.

(client response headers at: 'Connection' ifAbsent: [ '' ])

sameAs: 'close'.12. Entities, Content Readers and Writers

As mentioned before, ZnMessages (ZnRequests and ZnResponses) can hold an optional ZnEntity as body. By now we used almost all concrete

subclasses of ZnEntity:

ZnStringEntityZnByteArrayEntityZnApplicationFormUrlEncodedEntityZnMultiPartFormDataEntityZnStreamingEntity

Like all other fundamental Zn domain model objects, these can and are used both by clients and servers. All ZnEntities have a content type (a mime-type) and

a content length (in bytes). Their basic behavior is that they can be written to or read from a binary stream. All but the last one are classic, in-memory objects.

ZnStreamingEntity is special: it contains a read or write stream to be used once in one direction only. If you want to transfer a 10 Mb file, using a normal

entity, this would result in the 10 Mb being taken into memory. With a streaming entity, a file stream is opened to the file, and the data is then copied using

a buffer of a couple of tens of Kb. This is obviously more efficient. The limitation is that this only works if the exact size is known upfront.

Knowing that a ZnStringEntity has a content type of XML or JSON is however not enough to interpret the data correctly. You might need a parser to convert the

representation to Smalltalk or a writer to convert Smalltalk into the proper representation. That is where the ZnClient options contentReader and contentWriter are useful.

If the content reader is nil (the default), contents will return the contents of the response object, usually a String or ByteArray.

To customize the content reader, you specify a block that will be given the incoming entity and that is then supposed to parse the incoming representation, for example as below:

ZnClient new

systemPolicy;

url: 'http://zn.stfx.eu/zn/numbers.txt';

accept: ZnMimeType textPlain;

contentReader: [ :entity |

entity contents lines

collect: [ :each | each asInteger ] ];

get.

In this example, get (which returns the same as contents) will no longer return a String but a collection of numbers. Note also that by using systemPolicy

in combination with an accept: we handle most error cases before the content reader start doing its work, so it does no longer have to check for good incoming

data. In any case, when the contentReader throws an exception, it can be caught by the ifFail: block.

If the content writer is nil (the default), contents: will take a Smalltalk object and pass it to ZnEntity class' with: instance creation method.

This will create either a text/plain String entity or an application/octectstream ByteArray entity.

You could further customize the entity by sending

contentType: with another mime type. Or you could completely skip the contents: mechanism and supply your own entity to entity:.

To customize the content writer, you need to pass a one-argument block to the contentWriter: message. The block should create and return an entity. A theoretical example is given next.

ZnClient new

url: 'http://internet-calculator.com/sum';

contentWriter: [ :numberCollection |

ZnEntity text:

(Character space join:

(numberCollection collect: [ :each | each asString ])) ];

contentReader: [ :entity | entity contents asNumber ];

post.

Assuming there is a web service at http://internet-calculator.com where you can send numbers to, we send a whitespace separated list of numbers to its sum URI

and expect a number back. Exceptions occuring in the content writer can be caught with the ifFail: block.

13. Downloading, Uploading and Signalling Progress

Often, you want to download a resource from some internet server and store its contents in a file. The well known curl and wget Unix utilities are often used to

do this in scripts. There is a handy convenience method in ZnClient to do just that.

ZnClient new

url: 'http://zn.stfx.eu/zn/numbers.txt';

downloadTo: FileLocator imageDirectory.

The example will download the URL and save it in a file named numbers.txt next to your image. The argument to downloadTo: can be a FileReference or

a path string, designating either a file or a directory. When it is a directory, the last component of the URL will be used to create a new file in that directory.

When it is a file, that file will be used as given. Additionally, the downloadTo: operation will use streaming so that a large file will not be taken into

memory all at once, but will be copied in a loop using a buffer.

The inverse, uploading the raw contents of file, is just as easy thanks to the convenience method uploadEntityFrom:. Given a file reference or a path string, it

will set the current request entity to a ZnStreamingEntity reading bytes from the named file. The content type will be guessed based on the file

name extension. If needed you can next override that mime type using contentType:. Here is a hypothetical example uploading the contents of the file

numbers.txt using a POST to the URL specified, again using an efficient streaming copy.

ZnClient new

url: 'http://cloudstorage.com/myfiles/';

username: '[email protected]' password: 'asecret';

uploadEntityFrom: FileLocator imageDirectory / 'numbers.txt';

post.

Some HTTP operations, particularly those involving large resources, might take some time, especially when slower networks or servers are involved. During

interactive use, Pharo Smalltalk often indicates progress during operations that take a bit longer. ZnClient can do that too using the signalProgress option.

By default this is off. Here is an example.

UIManager default informUserDuring: [ :bar |

bar label: 'Downloading latest Pharo image...'.

[ ^ ZnClient new

signalProgress: true;

url: 'http://files.pharo.org/image/stable/latest.zip';

downloadTo: FileLocator imageDirectory ]

on: HTTPProgress

do: [ :progress |

bar label: progress printString.

progress isEmpty ifFalse: [ bar current: progress percentage ].

progress resume ] ]14. Client Options, Policies and Proxies

To handle its large set of options, ZnClient implements a uniform, generic option mechanism using the optionAt:put: and optionAt:ifAbsent: methods

(this last one always defines an explicit default), storing them lazily in a dictionary. The method category options includes all accessors to actual settings.

Options are generally named after their accessor, a notable exception is beOneShot. For example, the timeout option has a getter named timeout and setter

named timeout: whose implementation defines its default

^ self

optionAt: #timeout

ifAbsent: [ ZnNetworkingUtils defaultSocketStreamTimeout ]

The set of all option defaults defines the default policy of ZnClient. For certain scenarios, there are policy methods that set several options at once. The

most useful one is called systemPolicy. It specifies good practice behavior for when system level code does an HTTP call:

ZnClient>>systemPolicy

self

enforceHttpSuccess: true;

enforceAcceptContentType: true;

numberOfRetries: 2Also, in some networks you do not talk to internet web servers directly, but indirectly via a proxy. Such a proxy controls and regulates traffic. A proxy can improve performance by caching often used resources, but only if there is a sufficiently high hit rate.

Zn client functionality will automatically use the proxy settings defined in your Pharo image. The UI to set a proxy host, port, username or password can be

found in the Settings browser under the Network category. Accessing localhost will bypass the proxy. To find out more about Zn's usage of the proxy settings,

start by browsing the proxy method category of ZnNetworkingUtils.

15. Conclusion

Zinc is a solid and very flexible HTTP library. This chapter only presented the client-side of Zinc i.e. how to use it to send HTTP requests and receive responses back. Through several code examples, we demonstrated some of the possibilities of Zinc and also its simplicity. Zinc relies on a very good object-centric decomposition of the HTTP concepts. It results in an easy to understand and extensible library.