11.5. The Chrome Registry and Locale

Your application is built and you're ready to upload your shiny new Mozilla program to your server for download. The last piece of the puzzle, locale versions, has been put in place. With the structures that Mozilla has in place, it no longer has to be an afterthought. Once you have the translated files, you need to make the decision about how you want to distribute your language versions, the languages you want to make available to the users, and the level of customization that you want to give to them.

In this section, we look at how the Mozilla application suite handles the chrome's locale component. Then you see how to apply these chrome registry structures and utilities on a more generic level for your application.

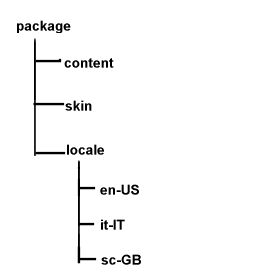

11.5.1. The Directory Structure

A typical application chrome structure looks like the directory structure in Figure 11-2. A folder for each language is under the locale directory. The general format is that each language has a unique identifier based on country code and the region. This conforms to the ISO-639 two-letter code with ISO-3166 two-letter country code standards.

| The W3C site has good resources that provide information about the ISO-639 and ISO-3166 standards at http://www.w3.org/International/O-HTML-tags.html. |

For example, the unique identifier for Scots, Great Britain, is Sc-GB. The first code, Sc, is for the Scots (Scottish) dialect, and the second code, GB, is for the country code for Great Britain. This is the standard that Mozilla follows.

The folder that is registered is the language folder, which is what has to be changed on an install. Thus, the URL chrome://package/locale actually points to package/locale/en-US or whichever language is turned on at the time. The language folder may in turn include subfolders that contain logical units for your application.

11.5.2. Interaction with the Chrome Registry

As pointed out in Chapter 6, your packages directories need to be registered as chrome with the chrome registry. The first step is to ensure that the entry for your package component is in the file chrome.rdf in the root chrome directory.

A resource:/ URL points to the folder for your files to be picked up and recognized by the chrome mechanism and accessed via chrome:// URLs in your application code. The locale is no exception.

<RDF:Description about="urn:mozilla:locale:en-US:xfly"

c:baseURL="resource:/chrome/xfly/locale/en-US/">

c:localeVersion="0.1.0.0"

<c:package resource="urn:mozilla:package:xfly"/>

</RDF:Description>A built-in versioning system in the chrome registry uses c:localeVersion descriptor, if you plan on distributing multiple language packs for your application. Other descriptors are available if you choose to use them: display name (c:displayName), internal name (c:name), location type (c:locType), and author (c:author).

11.5.3. Distribution

Language distribution may not be an issue for you. If, for example, your application were only going to be localized into a finite number of languages, bundling each of them up with the main installer would be most convenient. If, however, the need for new language versions arises at various intervals in the release process, you need to find a way to make them available and install them on top of an existing installation.

For example, as more people from various locations in the world are becoming aware of the Mozilla project, they want to customize it into their own language. Here are the steps that you need to take to set up your version.

Register as a contributor and set up the resources that you need, if any (web page, mailing list). This will ensure that you are added to the project page on the mozilla.org site.

Get a copy of Mozilla to test either via a binary distribution or by downloading and building your own source (see Appendix A for more information).

Translate the files.

Package your new files for distribution.

Test and submit your work.

Step 4, the packaging of the new language pack, is discussed next. Mozilla's Cross-Platform Install (XPI) is the ideal candidate for achieving this packaging. This method is discussed extensively in Chapter 6. This distribution method provides great flexibility and has the benefit of being native to Mozilla, thus bypassing the search for external install technologies for your application.

11.5.3.1. The anatomy of an install script

Example 11-9 presents a script that is based on the Mozilla process that distributes localized language packs. It presumes that there is a single JAR file for the language that is installed and registered in the Mozilla binary's chrome root.

The XPI archive consists of the JAR file in a bin/chrome directory and the install.js file, together in a compressed archive with an .xpi extension. Simply clicking on a web page link to this file invokes the Mozilla software installation service and installs your language. For convenience, inline comments in Example 11-9 explain what is happening.

By changing some values of the changeable fields, you can tailor this script to handle the install in any directory in the chrome (cf) that you want and register the chrome URL (localeName) for use. The rest is handled by the built-in functionality in XPI provided by such functions as initInstall and performInstall.

11.5.3.2. Switching languages

The mechanism for switching languages can take many forms. Mozilla switches languages by updating an RDF datasource when a language pack is installed. The UI for switching languages in Mozilla is in the main Preferences (Edit > Preferences). Within the preferences area, the language/content panel (Appearance > Languages/Content) interacts with the chrome registry when loaded, reading in the installed language packs and populating a selectable list with the available language identifier. Selecting one language and restarting Mozilla changes the interface for the user. Example 11-10 is a simple script for switching locales.

The language code is passed in as a parameter to the switchLocale JavaScript method in Example 11-10. The locale is set via the nsIChromeRegistry component, which uses a method named selectLocale. This locale selection is located in the first few lines, and the rest of the code prepares and shows a prompt to the user. This prompt reminds you to restart Mozilla to ensure that the new locale takes effect.